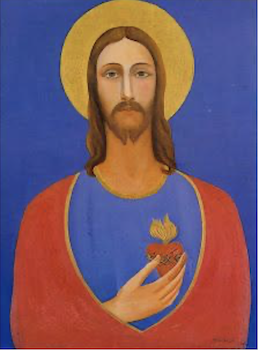

Tarsila do Amaral was born on September 1, 1886, in Capivari, a rural town in the Brazilian state of São Paulo. She was born the second of five children and spent much of her childhood with her parents, Lydia Dias de Aguiar do Amaral and José Estanislau do Amaral, on her family's prosperous coffee farm. As a teenager, Amaral was sent to São Paulo to study in a Catholic school, Colégio Sion. In 1904, at the age of 18, she completed her education in Barcelona, Spain, and produced her first painting, “Sagrado Coração de Jesus” (Sacred Heart of Jesus), a modernist reinterpretation of religious symbolism. When she returned to São Paulo in 1906, Amaral consolidated her studies and also married André Teixeira Pinto, giving birth to her only child, Dulce. Nonetheless, a few years later, the couple broke up.

In 1916, she immersed herself in sculpting with Danish-Brazilian sculptor William Zadig, who played a significant role in the Brazilian Modernist movement due to his contributions to public sculptures and influence on the development of modernist aesthetics in Brazil. In 1917, she began furthering her painting career in the studio of Pedro Alexandrino, a famous naturalistic Brazilian painter. During this time, Amaral became interested in modernism due to her meeting with the artist and dear friend Anita Malfatti, who pioneered this movement in Brazil. In 1920, she returned to Europe to study under the painter Émile Renard and at the Académie Julien in Paris, France, until June 1922. Throughout those three years, Amaral was inspired by Cubism, following in the footsteps of painters like Picasso. Hence, these artists were vital for Amaral’s creation of an art that was both pioneering and profoundly connected to her Brazilian roots.

Upon returning to São Paulo, Amaral had unfortunately missed the revolutionary “Semana da Arte Moderna” (the Week of Modern Art) on February 13-17, 1922, which she learned about through letters from Anita. Specifically, it consisted of lectures, readings, and exhibitions focused on Brazilian peculiarities, including mixed ethnicities and indigenous cultures. While in Brazil, Amaral was encouraged by Anita to join the modernist group to which she belonged. Together, Tarsila do Amaral, Anita Malfatti, Oswald de Andrade, Mário de Andrade, and Menotti Del Picchia were known as “O Grupo dos Cinco” (the Group of Five). They organized cultural meetings and conferences in São Paulo to promote Brazilian culture through modern art.

In December 1922, Amaral returned to Paris to study with André Lhote at Académie Lhote. Her boyfriend, Oswald de Andrade, joined her shortly thereafter. During this period, Amaral was further exposed to different types of modern art, such as Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism. At the same time, she was studying with the cubist master Fernand Léger. In a letter to her parents, she explained how her life in Paris had encouraged her to value her roots and how she wanted to be known as a Brazilian painter.

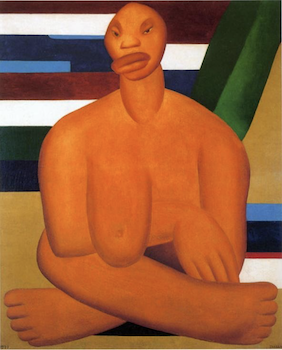

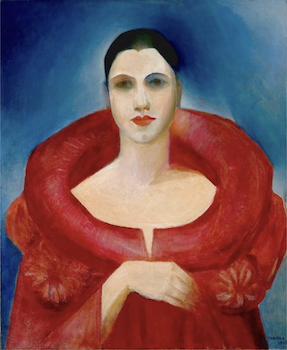

In 1923, Amaral created the masterpiece “A Negra” (The Black Woman), which represents Afro-Brazilian heritage and the cultural diversity of Brazil. Fernand was so impressed that he called his other students to see it. The year 1923 also influenced her social life. She got acquainted with the most influential cultural figures, such as Blaise Cendrars, Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso, and Constantin Brancusi, and hosted fancy “Brazilian dinners” for a selected crowd. One of these events inspired her to paint the self-portrait “Manteau Rouge” (Red Coat) in the same year, which reflected her desire for self-expression and the manifestation of a modernist identity.

In December of 1923, Amaral and Oswald returned to Brazil. Very soon, Blaise Cendrars joined them on a tour in Brazil, visiting Rio de Janeiro during Carnival and small towns in Minas Gerais during Holy Week. In Minas Gerais, she rediscovered the vibrant colors she used to enjoy as a child; however, she was later taught to reject them because they were seen as “ugly and of poor taste”. The trip also inspired her series of paintings “Pau-Brasil” (Brazilwood).

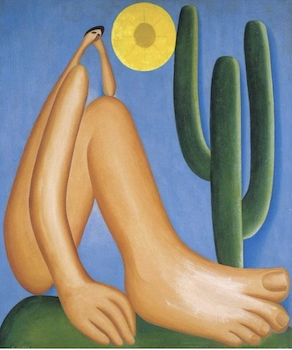

In January 1928, Amaral gave a special birthday gift to her husband Oswald: the painting “Abaporu” (Man Who Eats Man in the Tupí-Guaraní language), which depicts the creation of a unique Brazilian cultural identity. This masterpiece inspired Oswald to write the Anthropophagic Manifesto, and, with Amaral, they founded the Anthropophagic Movement. Also known as the “Cannibalist Movement,” it was characterized by the idea that Brazilian artists should “cannibalize” European influence to create a unique Brazilian masterpiece. That being said, Amaral advocated for the transformation of European cultural elements into a piece that would reflect Brazilian reality and identity.

In 1929, the New York Stock Exchange crashed, which caused a worldwide crisis that affected the price of coffee in Brazil and forced Amaral to adopt a humbler lifestyle. Despite this crisis, Amaral’s name continued to hold influence around the world and her works were exhibited in New York and Paris. However, her personal life took a greater toll. The following year her relationship with Oswald came to an end. This troubled period made Amaral switch depictions of nature to sociopolitical issues in her paintings.

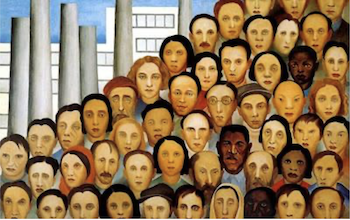

In 1931, Amaral started dating the communist doctor Osório Cesar. Both participated in the protest of the dictator Getúlio Vargas in 1932, resulting in their imprisonment the following year. After her liberation, the couple broke up and Amaral never got involved with politics again. The incident inspired her to paint “Operários” (Workmen) in 1933, which is a social commentary on the impact of industrialization and the conditions faced by the labor force. In the painting, the expressionless faces reflect the anonymity and dehumanization of factory work. Furthermore, Amaral’s works continued to convey social issues for the next two decades. In 1935, she started dating the writer Luís Martins, and the romance lasted 18 years. From 1936 until the mid-1950s, she worked as a columnist for the newspaper “Diários Associados”. She then settled in São Paulo in 1938, painting Brazilian people and scenery. Later on, in 1949, she lost her only granddaughter, Beatriz, who had drowned while saving a friend in a lake in Petropolis. In 1950, she returned to her semi-cubic style, depicting Brazilian landscape and imagery. Sixteen years later, in 1966, her only daughter passed away from complications of diabetes. After facing significant personal tragedies, Amaral started suffering from depression, dying due to mental health complications in 1973.

Amaral is best remembered for her painting “Abaporu”, which is displayed at the “Museo de Arte Latino-Americano de Buenos Aires” in Argentina. She revolutionized the world of art, leaving behind more than 230 works. To this day, her art is celebrated and inspires generations of artists with the Anthropophagic movement and the idea of cultural cannibalism. Amaral also influenced Brazilian modernism by helping to develop the indigenous Brazilian style. In honor of her, NASA attributed the name Amaral to a crater (The Amaral Crater) on Mercury. Amaral will forever be remembered as a pioneer of modernized art movements in Latin America and a leading female figure in defining a new “language” in the visual arts.

Why Did I Choose to Research Tarsila do Amaral?

I chose to research the life of Tarsila do Amaral because, although she is well-known in Brazil as an icon who revolutionized the nation’s arts, many people from other cultures do not know her work. I believe Amaral can teach us a lot about resilience, dedication, perseverance, and strength. Even after losing her daughter and granddaughter, Amaral continued to revolutionize the world of arts.

Works Cited

Apreender História. (2012, March 19). Material para sensibilização. Retrieved from Material para sensibilização https://apreenderhistoria.blogspot.com/2012/03/material-para-sensibilizacao.html

Artverlaine. (2022, February 13). Tarsila do Amaral: the Modernist Painter of Brazil. Retrieved from Tarsila do Amaral: the Modernist Painter of Brazil – Artverlaine

Aventuras na História. (2022, February 14). Entre a Arte e as Traições: Conheça os maiores amores de Tarsila do Amaral. Retrieved from https://aventurasnahistoria.uol.com.br/noticias/vitrine/historia-os-amores-de-tarsila-do-amaral.phtml

EBiografia. (2021, February 09). 12 obras para saber mais sobre Tarsila do Amaral. Retrieved from 12 obras para saber mais sobre Tarsila do Amaral - eBiografia

Escola Municipal Tarsila do Amaral. (2012, September 17). Quem foi Tarsila do Amaral? Retrieved from Escola Municipal Tarsila do Amaral

HipCrave. (2018, February 01). Tarsila do Amaral´s Exhibit Brings Brazilian Modern Art to the MoMA. Retrieved from Tarsila Do Amaral’s Exhibit Brings Brazilian Modern Art to the MoMA - HipCrave

Tarsila do Amaral. Biography: Know the history of the artist Tarsila do Amaral. Retrieved from Biography - Tarsila do Amaral

The Famous People. Tarsila do Amaral Biography. Retrieved from Tarsila do Amaral Biography - Facts, Childhood, Family Life & Achievements of Brazilian Artist thefamouspeople.com

Toda Matéria. Abaporu: pintura de Tarsila do Amaral. Retrieved from https://www.todamateria.com.br/abaporu/

Vírus da Arte e Cia. (2016, March 08). Tarsila – A NEGRA. Retrieved from Tarsila – A NEGRA - VÍRUS DA ARTE & CIA. https://virusdaarte.net/tarsila-a-negra/

World Information DB. (2022, August 29). Who is Tarsila do Amaral (1883 – 1976). Retrieved from Who is Tarsila do Amaral (1883-1976) - World Information DB

This article was published on 7/25/24