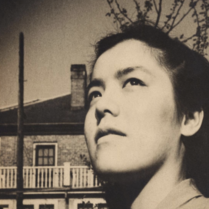

Grace Lee was born on June 27, 1915 above her father’s Chinese restaurant in Providence, Rhode Island, United States. Her family moved to Jackson Heights, a diverse neighborhood in New York, when she was young. Lee’s father was a successful restaurateur and later owned a popular Chinese restaurant near Times Square. Her mother, Yin Lan, served as a feminist inspiration to the receptive Lee. Lan never learned to read or write since females were denied education in her small Chinese village. This sparked outrage in Lan, who passed her belief in gender equality onto Lee. “My mother was a rebel all her life,” Boggs recalled in a 1993 speech in front of the Asian Pacific American Women’s Symposium.

Lee was an avid scholar and obtained a scholarship to Barnard College when she was 16 years old. She graduated with a degree in philosophy in 1935. Five years later, she received her Ph.D., again in philosophy, from Bryn Mawr College. Heavily influenced by the writings of theorists Mead and Hegel, Lee was determined to solve the problems of inequality women and minorities face. Although she wanted to teach political philosophy or ethics, she found that not a single college wanted to hire a Chinese woman to teach either subject. ‘We don’t hire Orientals,’ Lee remembered hearing frequently, recalling the anti-Chinese and anti-Asian sentiments of the 1940’s. Discouraged, she ultimately settled for a library job at the University of Chicago.

In Chicago, Lee struggled to make ends meet as she lived off her $10-per-week stipend. Not able to afford housing, she lived in a rat-infested basement for free. As she walked through her neighborhood one day, she approached a small protest demanding for better living conditions. Lee thought about her own living situation and quickly realized that she could support this movement. Soon after, she joined the tenant’s rights campaign where she began to organize protests against poor housing conditions. During this time, she published her first book, George Herbert Mead: Philosopher of Social Individualism, and translated essays written by Karl Marx in his Economical and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 from German into English. She found her way into the Socialist Workers Party and one of its sects, the Johnson-Forest Tendency: a group of factory workers who met at night to debate political theory. Lee wrote propaganda pamphlets and articles for the Johnsonite (Johnson-Forest Tendency led) newspaper, the Correspondence, under the pen name Ria Stone.

In 1953, Grace Lee moved to the Johnsonite stronghold of Detroit. That same year, she met James Boggs, an African-American factory worker and fellow Johnsonite. They married and she took his surname, becoming Grace Lee Boggs. Prior to Detroit, Boggs had lent her activism to the first March on Washington in 1941. The successful movement led to the establishment of the Fair Employment Practices Committee under Executive Order 8802. As a result, African-Americans were able to secure more federal government and national defense jobs. Boggs then turned her focus onto the Civil Rights Movement with an emphasis on Black Lives Matter. “Thirteen million Negroes in America have never known three of the ‘Four Freedoms’ which America is supposedly spreading to the rest of the world,” she asserted. She began hosting meetings at her home where Malcolm X gave Black empowerment speeches to small audiences. She attempted to persuade him into running for the US Senate in 1964 but was ultimately unsuccessful. Boggs liked to joke that the FBI must’ve assumed she was Black herself for all the Black activism she accomplished. She is one example of the many Asian-American activists who have helped amplify and strengthen the voices of the Black community.

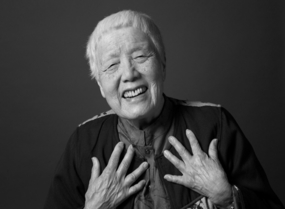

In 1992, Boggs and her husband established Detroit Summer, an organization that connected neighbors of all ages and cultures to rebuild their city by creating public murals, renovating houses, and planting community gardens in abandoned lots. Boggs considered Detroit “a symbol of the end of industrial society” and worked to reconstruct the city through Detroit Summer. In 2013, she established the James and Grace Lee Boggs School with a curriculum designed to challenge students’ thinking and community-problem solving skills. Her legacy is carried on by the Boggs Center, which continues to initiate community-based social activism projects.

Throughout her life, Boggs remained an active supporter of the Asian American Movement. She helped establish the Detroit Asian Political Alliance in 1970, which fought for social and political acceptance of Asians. The Alliance’s pan-Asian ideology helped create a unified community with members of all Asian backgrounds. Additionally, she continually pushed for feminist movements throughout the world. Never forgetting her mother’s lack of education, Boggs has been persistent in supporting female learning institutions, particularly in China. “It’s very amazing that up to now we don’t have any idea what feminism in China is going to mean,” Boggs remarked. After publishing her autobiography in China, she hoped that other women would take up the fight for gender equality.

Today, Boggs is remembered for her philosophy that change starts with small community groups, as opposed to large revolutions. She fought hard for tenant rights and environmental justice. She was devoted to the social and economic welfare of women and minorities, especially Asian Americans and African Americans. She wrote a memoir outlining her life and her legacy, Living For Change: An Autobiography, and is featured in the documentary American Revolutionary: The Evolution Of Grace Lee Boggs. She died on October 5, 2015 after turning 100 years old.

Why Did I Choose to Research Grace Lee Boggs?

I chose to research and write about Grace Lee Boggs because she embodies my definition of a model citizen: always putting others before herself, taking action to reform her community and country, and supporting other minorities in need. She has inspired me to embrace my own culture while serving others. I only wish that she could’ve lived to witness the social revolution today for the black lives that she dedicated her life to fighting for.

Works Cited

Americans Who Tell The Truth Editors. (n.d.). Grace Lee Boggs. Retrieved from http://www.americanswhotellthetruth.org/portraits/grace-lee-boggs

Liu, R. (2018, November 15). Reading Event Honors Social Activist Grace Lee Boggs. Retrieved from https://cornellsun.com/2018/11/15/reading-event-honors-social-activist-grace-lee-boggs/

Mai-Duc, C. (2015, October 07). Grace Lee Boggs: Words of wisdom from 70 years of activism. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/nation/nationnow/la-na-nn-grace-lee-boggs-quotes-20151006-htmlstory.html

McFadden, R. (2015, October 5). Grace Lee Boggs, Human Rights Advocate for 7 Decades, Dies at 100. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/06/us/grace-lee-boggs-detroit-activist-dies-at-100.html

Sugrue, T. (2017, June 19). Postscript: Grace Lee Boggs. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/postscript-grace-lee-boggs

This article was published on 6/7/20