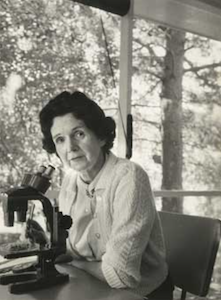

Rachel Louise Carson was an American marine biologist, writer, and conservationist. She was born on May 27, 1907, on her family’s 64-acre farm near Springdale, Pennsylvania to Maria McLean and Robert Warden Carson. From a young age, she developed a strong interest in learning about the world around her. Carson began her education at the Pennsylvania College for Women with aspirations to be a writer. However, she was convinced by Mary Scott Skinker, a biology professor, to change her field of study to biology.

In 1929, Carson furthered her education by doing graduate work at John Hopkins University, and earned an M.A in zoology in 1932. She originally intended to pursue a doctorate degree at John Hopkins University, but held back her academic career in order to support her family during the Great Depression.

After the urging of her mentor Mary Scott Skinker, Carson took a temporary position in the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, writing radio scripts for a series of weekly educational broadcasts, named “Romance Under the Waters.” Around this time, Carson began submitting articles about marine life to local newspapers and magazines. Following the success of her radio series, she was asked to write an introduction for an article about the fisheries bureau. She also sat for the civil service exam, on which she outscored all other applicants. In 1936, Carson became the second woman (in history) hired by the Bureau of Fisheries for a full-time position, setting off her professional journey as an aquatic biologist. She worked in the department until 1952, as the Editor in Chief of the service’s publication for the last three years before her retirement.

In 1937, the Atlantic Monthly accepted an edited version of an essay that she had previously written for their first brochure. The essay was titled, “The World of Waters,” and marked a turning point in Rachel’s scientific writing career; it led to the publishing house Simon & Schuster requesting her expansion of the essay into a book. The book was published in 1941 and named “Under the Sea-Wind.” It received high ratings for its scientific accuracy and compelling delivery. Her next book, “The Sea Around Us,” was published in 1951, and became a national bestseller (it won a National Book Award and the John Burroughs Medal). The book was widely acclaimed and, as a result of its exceptionality, Carson was awarded two honorary doctorates. Her third book, “The Edge of the Sea,” was published in 1955.

Carson’s most impactful book is “Silent Spring,” which was published in 1962, and was first serialized in The New Yorker, later becoming a bestseller. The book detailed the detrimental effects of pesticides on the environment, arguing that they should be termed “biocides,” since they do not only target pests. For example, DDT, also known as Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, is one of these harmful pesticides that was aerial sprayed across the world to kill pests. It was later labeled as problematic, due to its prolonged environmental impacts. The title of the book, “Silent Spring,” is a metaphor for the bleak future of nature with the unrestricted use of pesticides.

Carson was first made aware of DDT, known as the “insect bomb,” after atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagaski in 1945. The pesticide, though widely praised, had not been thoroughly tested for safety and ecological effects. The United States Federal Government’s program for the eradication of the Gypsy Moth, led Carson to devote time and energy into researching pesticides and environmental poisons. Carson and many other scientists presented their findings to the public about the consequences of using pesticides; after this unveiling, Carson met harsh opposition from the chemical industry. Despite these attacks, Carson stood her ground, with the science community supporting her. While battling cancer, she testified in front of President John F. Kennedy’s Science Advisory Committee, and they subsequently issued a report backing her scientific claims.

Rachel died on April 14, 1964, at the age of 56, from breast cancer. She was unmarried with an adopted son Roger Christie, who was also her grandnephew. Though Carson passed away before she could see any concrete results of her work, she (and her efforts) had a powerful impact on the global grassroots environmental movement. The most notable outcome of her research is the prohibition of DDT use in the United States (with the exception of emergencies in 1972). She was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Jimmy Carter. We should collectively thank Carson’s work for the ban on DDT, the high standards for pesticide use, and the growing ecological movement. Her work not only laid the foundation for the contemporary concept of environment protection, but also had a profound impact on our natural world, paving the way for the implementation of worldwide restrictions on pesticide use. Her legacy remains in the establishment of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (created on December 2, 1970). Overall, Rachel Carson’s contributions to the field have inspired countless scientists, activists, and everyday people to strive for a future, where the world does not become a “Silent Spring.”

Why Did I Choose to Research Rachel Carson?

Rachel Carson was one of the driving forces behind the conception of the modern environmentalist movement in the 1960s, having made significant contributions to environmental research. I was first introduced to Rachel Carson when I was fourteen through her book “Silent Spring.” This reading prompted me to learn more about pesticide use. Her work has brought forth numerous progressive policies that can lead us towards a more eco-conscious future. Rachel Carson’s journey inspires women to speak their truths, even when people will inevitably berate them for daring to share their perspectives, and is proof of the impact we can make by doing so.

Works Cited

Bradford, A. (2018, March 31). Rachel Carson: Life, discoveries and legacy. LiveScience. Retrieved May 22, 2022, from https://www.livescience.com/62185-rachel-carson-biography.html.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2022, April 10). Rachel Carson. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 22, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Rachel-Carson.

Carson, R. 1907-1964. (1962). Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin.

Griswold, E. (2012, September 21). How 'Silent spring' ignited the environmental movement. The New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/23/magazine/how-silent-spring-ignited-the-environmental-movement.html.

Lear, L. (1996). Rachel Carson's biography. Rachel Carson, Biography. Retrieved May 22, 2022, from http://rachelcarson.org/Bio.aspx.

Leonard, Jonathan. (1964). Rachel Carson Dies of Cancer; 'Silent Spring' Author Was 56. New York Times. Retrived May 22, 2022, from https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/97/10/05/reviews/carson-obit.html?_r=1.

Michals, D. (2015). Rachel Carson. National Women's History Museum. Retrieved May 22, 2022, from https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/rachel-carson.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). DDT - A Brief History and Status. EPA. Retrieved May 22, 2022, from https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/ddt-brief-history-and-status.

This article was published on 8/1/22