Eunice Hunton Carter was born on July 16th, 1899 in Atlanta, Georgia. Carter was born to William Alphaeus Hunton Senior, an international secretary for the YMCA, and Addie Waites Hunton, a prominent social justice advocate and organizer for the YMCA and NAACP. In addition, she had one younger brother, Alphaeus Hunton. Briefly living in Georgia, they relocated to Brooklyn, New York after the 1906 Atlanta race riots. The Atlanta race riots of 1906 happened on September 22, 1906. Between 12 to 25 African Americans were killed, racial tensions and news articles agitated white mobs to attack Atlanta’s Brownsville district. The effects on neighborhood structures lasted long after the rampage due to the mobs setting buildings on fire.

Among her family, Carter was someone who appreciated the value of service and social justice. Carter’s inclination towards law can be cited back to the age of eight. In her childhood, after her home was destroyed in the riots, she told another child that she would put the bad people behind bars and be a lawyer. However, she was not alone in this endeavor towards social justice, in fact, her mother gave support to Black troops in World War I in France and was a prominent activist internationally in racial equality. Likewise, her father assisted majorly in the desegregation of YMCAs in the South, showcasing how her values came to be.

After her childhood in New York, Carter attended Smith College, a prestigious women’s college in Northampton, Massachusetts, where she earned her bachelor's and master's degree in social work. As a scholar who put value in knowledge, Carter was the second woman at Smith College who was able to complete both these degrees in four years. In the 1920s, she came to be involved in a predecessor of the United Nations, the Pan-African Congress, where she and other countries' delegates would discuss present issues in Africa. In 1924, she married Lisle Carleton Carter, a dentist who immigrated to America from Barbados; they had one child together named Lisle Carter Junior.

Dreaming of a career in law, Carter worked full time as a supervisor to Harlem’s Emergency Unemployment Relief Committee while graduating from Fordham Law School in 1932, being one of the first black women to graduate from Fordham Law.

Demonstrating her love for law and government service, Carter ran as a Republican candidate for New York’s Nineteenth Assembly District in 1934. While it was an unsuccessful attempt, the experience led her to land a job that exhibited her intelligence as a lawyer that we know her for today.

During her fruitful career, she trail-blazed by becoming the first black female assistant district attorney in the state of New York in 1935, working as a prosecutor to the New York County, specifically Manhattan, office. Carter was appointed to the women’s court by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, where she worked with women involved in prostitution.

While she worked, Carter realized that there was a common pattern between all the cases: most of the defendants had often told the same stories, even having the same bondsmen and representation. Moreover, Abe Karp, a disbarred lawyer rumored to have connections to a criminal organization, would show up at these trials, leading to officers forgetting key details. This usually ended in the women being acquitted of the charge.

Carter brought this information up to Thomas Dewey, a special prosecutor for New York. Then, she joined Dewey’s team dubbed “Twenty Against the Underworld” where she was the only member who was not a white male. With her theory and help from colleague Murray Gurfein, she convinced Dewey to wiretap the offices of the bondsmen who were involved with the women’s court daily.

Her in-depth research laid the foundation for her understanding of the fact that organized crime had hijacked brothels throughout the city, making them pay a bond fee for protection from legal mishaps. Eventually, the wiretaps led her to Charles “Lucky” Luciano, one of the most influential and infamous mob bosses in New York City, through a string of connected individuals. In February of 1936, she overlooked a raid of about 80 brothels in New York City, bringing hundreds of individuals with valuable information in. Carter led these interviews and convinced a few to divulge names of individuals connected to Luciano’s name. Carter’s actions majorly contributed to the ultimate sentencing of Luciano of 30-50 years in 1936. However, Luciano did get deported to Italy eleven years later in exchange for preventing problems at the New York City Docks during World War II.

After locking up the Luciano case, she was appointed Chief of the Special Sessions Bureau in 1937. Her department dealt with over 14,000 cases a year and she became one of the highest-paid African-American lawyers in the country.

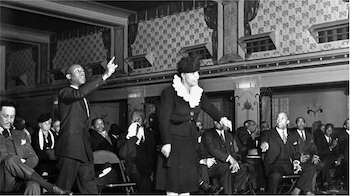

As a devoted individual to service, Carter was active in the United Nations. She was present during the founding session of the United Nations and was also a consultant for the U.N Social and Economic Council for the International Council of Women. Championing gender and human rights, she focused much of her energy on improving the U.N. Commission on the Status of Women. Furthermore, she was an active figure in these assemblies and conferences, discussing and advocating for the rights of women. In 1955, she was elected to be chair of the UN's International Conference of Non-Governmental Organizations, the highest post ever held by a woman at the time.

Carter died on January 25, 1970 at 70 years old in New York City. Her influence is felt as a woman who prevailed against the circumstances of the time. She inspired many, including her colleague Thomas Dewey, who ran on the strongest civil rights platform ever adopted by a major party at the time largely due to her influence. Her story is also told through print, specifically in a book by her grandson Stephen L. Carter titled: Invisible: The Forgotten Story of the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took Down America's Most Powerful Mobster. Her legacy persists through her fight for gender equality in international service, conversing about and advocating for the topic. Moreover, she helped break barriers for women to advance in international service. Carter is an example of determined intellect in service. Notably, Carter’s perseverance and intelligence serves as a beacon of motivation for others, influencing their everyday endeavors.

Why Did I Choose to Research Eunice Hunton Carter?

As a lover of true crime documentaries, I was absolutely amazed at Carter’s accomplishments and saddened by how I did not know of them before. Not only was she dedicated to government service here in the United States, but she was involved with the United Nations as well, which I admire greatly. She paved the way for other lawyers in New York and will forever be known as a pioneer for women in her field. I am inspired by her intellect in bringing Lucky Luciano down, and I wanted others to be inspired by Carter’s commitment to justice.

Works Cited

CBS News. (2018, October 20). How Eunice Carter helped take down one of America's most notorious mob bosses. CBS News. Retrieved July 30, 2024, from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/eunice-carter-black-lawyer-who-took-down-one-of-americas-most-notorious-mob-bosses/

Eunice Carter. (n.d.). Fordham School of Law. Retrieved July 30, 2024, from https://www.fordham.edu/school-of-law/alumni/alumni-of-distinction/eunice-carter/

Eunice Carter. (n.d.). The Mob Museum. Retrieved July 23, 2024, from https://themobmuseum.org/notable_names/eunice-carter/

Historical Society of the New York Courts. (2021, October 27). Eunice Hunton Carter. Historical Society of the New York Courts. Retrieved July 30, 2024, from https://history.nycourts.gov/eunice-hunton-carter/

National District Attorneys Association. (2024, February 21). Eunice Carter: The trailblazing prosecutor who helped take down Lucky Luciano. Medium. Retrieved July 30, 2024, from https://ndaajustice.medium.com/eunice-carter-the-trailblazing-prosecutor-who-helped-take-down-lucky-luciano-f7b0e13b5c92

Ott, T. (2022, January 19). Eunice Hunton Carter: The woman who reeled in Lucky Luciano. Biography.com. Retrieved July 23, 2024, from https://www.biography.com/crime/eunice-hunton-carter-lucky-luciano

Weinman, S. (2018, December 7). The real-life heroine who inspired a character on 'Boardwalk Empire'. The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2024, from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/07/books/review/invisible-stepehn-carter-eunice-hunton-carter-biography.html

Degregorio, E. (2021, August 10). New biography of Eunice Carter '32 explores her lifelong fight for social justice. Fordham Law News. Retrieved August 1, 2024, from https://news.law.fordham.edu/blog/2021/08/10/new-biography-of-eunice-carter-explores-her-lifelong-fight-for-social-justice/

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (n.d.). Atlanta race riot of 1906. Britannica. Retrieved August 5, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/event/Atlanta-Riot-of-1906

This article was published on 8/30/24