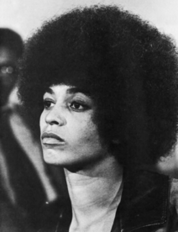

Angela Yvonne Davis was born on January 26, 1944, in the city of Birmingham, Alabama, United States. She grew up with her parents and three siblings in a middle-class neighborhood known as “Dynamite Hill.” White civilians, in her neighborhood, opposed the integration of Black people so strongly that they bombed several Black-owned homes in attempts to drive them out, thus warranting the neighborhood’s nickname.

Growing up, Davis participated in Sunday school, church youth group, and the Girl Scouts. She was constantly surrounded by activists and leaders who challenged the social norms and demanded justice. When she was fifteen years old, she and her fellow Girl Scouts picketed in Birmingham to protest racial segregation. Davis’s mother, Sallye, was an elementary school teacher and a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Southern Negro Youth Congress. Sallye was an avid scholar whose desire for education Davis inherited. By the time Angela was a high school junior, she was accepted to the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker institution that connected Southern Black students with integrated schools in the North.

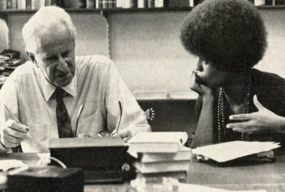

Davis began attending Brandeis University on scholarship in 1961, as one of the only three Black students in her class. There, she met Herbert Marcuse, a political theorist most notably associated with the Frankfurt School of Marxism, during a rally regarding the Cuban Missile Crisis. She became his student and later reflected, “Herbert Marcuse taught me that it was possible to be an academic, an activist, a scholar, and a revolutionary.” Under Marcuse, she became progressively involved in far-left politics and became a Marxist feminist, an advocate against the ways women are exploited through capitalism and private ownership of property. It was in college that Davis discovered more communist contacts and attended communist-sponsored events such as the 1962 World Festival of Youth and Students in Helsinki, Finland. Although the convention promoted democracy and denounced imperialism and war, the Federal Bureau of Investigation detained and extensively interviewed Davis after her return to the United States. The ordeal did not stop her from joining the Che-Lumumba Club, an all-Black chapter of the Communist Party in America, during her years as a graduate student at the University of California, San Diego.

She was studying French abroad at the Sorbonne when she received news of the 1963 Birmingham Church Bombing initiated by the Ku Klux Klan, an American terrorist group of white supremacists. Davis had been friends with the four girls who died and mourned their deaths deeply. She was also abroad in Germany when she learned about the establishment of the Black Panthers Party. She was briefly introduced to Black activists Stokely Carmichael and Michael X (not to be confused with Malcolm X) during a trip to England. Although she respected her colleagues’ fight for civil justice, she did not fully agree with their Black nationalist ideals and was disappointed by their rejection of communism for the reason that it was a “white man’s thing.”

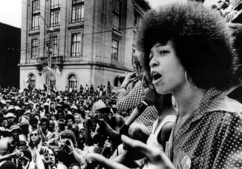

By the time she was twenty-five years old, she was known as a “radical” activist, feminist, Black Panther affiliate, and member of the Communist Party. She received several teaching offers from schools, including Princeton and Swarthmore, but she finally chose the University of California, Los Angeles. Unbeknownst to her, the University of California Board of Regents passed a policy against hiring communists in 1949. Just months after she began teaching, the UC Board fired Davis under pressure from then-Governor Ronald Reagan. Davis fought a legal case to win back her post and succeeded. Nine months later, she was fired once more for using “inflammatory language” in speeches, notably and repeatedly referring to the police as “pigs.” Again, she was given back her position after the American Association of University Professors rebuked the UC Board of Regents and taught until her contract expired in 1970.

Despite the public legal battle, Davis is most remembered for her involvement with the Soledad Brothers, which led to her arrest and trial. She was an outspoken supporter of three Black Soledad Prison inmates accused of killing a prison guard after a second guard killed several Black inmates. Like many others, she believed the Brothers, who were not related by blood, were scapegoats of criminal justice politics. During a court session in October 1970, the biological brother of inmate George Jackson seized control of the courtroom and took several hostages in an attempt to free the Brothers. Police fired into the getaway vehicle, killing the judge and Soledad Brothers while injuring hostages. The crime investigation discovered that Jackson had used firearms purchased by Davis two days prior to the court session. Evidence that she had corresponded with one of the inmates was also uncovered. Subsequently, she was charged with kidnapping and first-degree murder. Davis became the third woman to be listed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitive List. By the time she was found in September, she had already fled across the country. President Richard Nixon praised the investigation team for its “capture of the dangerous terrorist Angela Davis.”

In January 1971, she appeared at the same Marin County Superior Court in yet another highly televised occasion. “I am innocent of all charges which have been leveled against me by the state of California,” Angela Davis declared to the nation. She had spent the past months in solitary confinement in a women’s detention center until her attorneys transferred her out of isolation. John Abt, a former counsel of the Communist Party, was the first lawyer to represent her. Meanwhile, civilians across the country demanded for her release. Committees both nationally and internationally organized to protest her incarceration. Musicians chimed in with political songs referencing Davis: The Rolling Stones’s “Sweet Black Angel”; Bob Dylan’s “George Jackson”; Todd Cochran’s “Free Angela (Thoughts… and all I’ve got to say)”; and John Lennon’s “Angela.” Ultimately, in June 1972, she was acquitted of all charges. Davis and her supporters accused Reagan and Nixon’s administration of suppressing antiracist and anticapitalist movements. Ever since, Davis has vigorously defended Black, female, and lower-class people from exploitation, racial discrimination, and wrongful incarceration.

Today, she is the author of several books concerning feminism, class struggles, Black rights, poverty, and prison reform. She has received honorary doctorates from Moscow State University and the University of Leipzig, as well as an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from the California Institute of Integral Studies. She was named Time magazine’s honorary 1971 Woman of the Year and was inducted into the Women’s Hall of Fame in 2019. She continues to lecture ethnic, feminist, and Black studies for various colleges and is a Professor Emerita of the History of Consciousness and Feminist Studies Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Davis is a co-founder of Critical Resistance, an organization committed to abolishing the prison industrial complex. Additionally, she works with international groups such as Sisters Inside, an Australian-based group aiding imprisoned women. Throughout her life, she has supported underrepresented groups when no one else would. She believed in social reform for the equality of civilians from every race, gender, religion, economic background, and political ideology. The title of her newest book reflects both her purpose and passion: Abolition. Feminism. Now.

Why Did I Choose to Research Angela Davis?

I chose to research Angela Davis because she is a living example of the oppression faced by minorities in America to this day. She was not afraid to publicize her philosophies, even at a time when subscribing to a different ideology meant persecution. She embodies the struggle for Black Power, social justice, feminism, and criminal justice. She continues to demand freedom for the thousands of suppressed people globally. As human beings, we can all learn something from Angela Davis.

Works Cited

Kendi, I. X. (2020, March 05). Angela Davis: 100 Women of the Year. Retrieved May 31, 2020, from https://time.com/5793638/angela-davis-100-women-of-the-year/

History.com Editors. (2009, November 09). Angela Davis. Retrieved May 31, 2020, from https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/angela-davis

Biography.com Editors. (2020, March 02). Angela Davis. Retrieved May 31, 2020, from https://www.biography.com/activist/angela-davis

SpeakOut Editors. (n.d.). Davis, Angela. Retrieved May 31, 2020, from https://www.speakoutnow.org/speaker/davis-angela

Petersen, S. (2017, April 24). Angela Davis and the Marin County Courthouse Incident. Retrieved May 31, 2020, from http://blackpower.web.unc.edu/2017/04/angela-davis-and-the-marin-country-courthouse-incident/

This article was published on 11/30/20