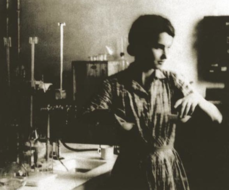

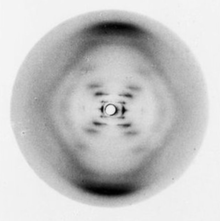

Rosalind Elsie Franklin was a pioneer in many fields. A physical chemist and X-ray crystallographer by trade, she applied her knowledge to diverse pursuits and radically changed almost all scientific fields. Franklin is best known for her work in DNA, where she took the first photograph to ever show the structure of a DNA molecule as being helical. She and her graduate student, Raymond Gosling, took the photograph, deemed “Photo 51,” in 1953. She also made discoveries in physical chemistry and virology that significantly advanced these fields. Franklin, who unfortunately passed away before she could be honored for her work, is now a role model to people everywhere.

Rosalind was born in London in 1920 into an affluent Jewish family. She received her secondary school education from St. Paul’s Girls School, where she excelled in many subjects. At the age of fifteen, she decided that she wanted to be a scientist because she was passionate about understanding the natural world. In 1938, she enrolled in Newnham College, Cambridge, where she studied chemistry and received Second Class Honors for her finals. Franklin went on to pursue a Ph.D. at the British Coal Utilisation Research Association focused on her work studying the porosity of coal— the holes in coal and their structure. Her early years as a scientist were filled with success, as she was regarded as an authority in the field. Franklin once stated, “science and everyday life cannot and should not be separated,” and believed her work to be the primary focus of her life.

In 1946, Rosalind Franklin was appointed as a researcher at the Laboratoire Central des Services Chimiques de l'Etat in Paris. She spent this time working with the crystallographer Jaques Mering and enjoying her time in Paris, convinced that it was the city for her. At this job, she learned to perform X-ray diffraction, using X-rays to identify different chemicals, which would become the basis for most of her work. She pioneered the use of X-rays in the analysis of complex and unorganized matter as well as pinpointing where atoms were located.

In 1951, Rosalind moved from Paris back to London, where she began her position as a biophysics research associate at King’s College, Cambridge. Under the direction of John Randall, a lab director and scientist himself, she applied her knowledge of X-ray diffraction techniques to the mysterious fibres of DNA molecules. Along with her graduate student Raymond Gosling, she came to a revelation that DNA had two forms, the A form and the B form, the A form being slightly more unwound than B form, the typical double-helix. Her primary focus was on the A form of DNA, however, she took photos of both. At the time, a race to uncover the structure of the secret of life was underway, and many scientists desired to be the first. A few years into this job, Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling took the clearest photo that had ever been seen of the B form of DNA using her vast knowledge of X-ray photography. The photo showed the helical structure of DNA molecules, in fact, it was a double helix. This photo was shown by her colleague Maurice Wilkins to other researchers, James Watson and Francis Crick, who drew the same conclusions as she did. Unfortunately, their work on the matter was published first, and Franklin never was recognized for her contributions during her lifetime. Due to hostility in her workplace, she eventually left.

After Franklin left King’s College, she worked at Birkbeck College in 1953 under John Desmond Bernal, her lab director who had a reputation for being a great scientist. She studied the structure of the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), a plant virus, and the structure of RNA, the nucleic acid that works along with DNA to produce proteins. Franklin discovered that the structure of the virus consisted of proteins wound around a core of RNA. These were some of Franklin’s most fruitful years in terms of her work, and she traveled to the United States to lecture and collaborate on two occasions. In five years, she published 17 papers on viruses and her group’s work greatly advanced the study of virology.

Rosalind Franklin worked through illness, developing ovarian cancer in 1956 and researching TMV until her death on April 16th, 1958. She lived for her work and persevered through painful circumstances, an example of her unwavering strength. After her death, James Watson, Maurice Wilkins, and Francis Crick were awarded the Nobel prize in physiology or medicine. Since the prize wasn’t allowed to be awarded posthumously, Franklin was never honored in this way. However, she has since been recognized for her work in various ways. For example, the building she worked in at King’s College has been named after her and Wilkins. However, James Watson has continued to deny that her helpful contributions led to his and Crick’s identification of the molecule’s structure. She was referred to in Watson’s book The Double Helix with various sexist terms and her brilliance was ignored.

Today, the scientific world has acknowledged Franklin’s essential role in the fields of genetics and molecular biology, but in many schools, students are still only taught about the discoveries of James Watson and Francis Crick. Rosalind Franklin was a brilliant scientist who dedicated her life to advancing diverse scientific fields with her vast knowledge, but never received full recognition for her contributions.

Why Did I Choose to Research Rosalind Franklin?

I chose to research Rosalind Franklin because I deeply believe, as someone who is interested in the field of genetics, that Franklin’s discoveries and work need to be remembered. She has led to great advancements in many fields, from medicine to engineering, and is an important historical figure.

Works Cited

Rosalind Franklin: A Crucial Contribution | Learn Science at Scitable. (2014). Nature.Com. https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/rosalind-franklin-a-crucial-contribution-6538012/

Biographical Overview. (2019, March 12). Rosalind Franklin - Profiles in Science. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/kr/feature/biographical

Maddox, Brenda. Rosalind Franklin : The Dark Lady of DNA. New York: HarperCollins, 2002.

Rosalind Elsie Franklin: Pioneer Molecular Biologist. (2020). Sdsc.Edu. https://www.sdsc.edu/ScienceWomen/franklin.html

Rogers, R. (2019). Rosalind Franklin. Rosalindfranklinsociety.org. https://www.rosalindfranklinsociety.org/rosalind-franklin

This article was published on 10/12/20