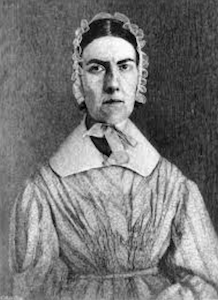

Angelina Grimke Weld was possibly one of the most progressive women of her time. Born in Charleston, South Carolina in 1805, Grimke was the youngest of 14 children. She grew up on a plantation and enjoyed the luxuries of being born into a wealthy family. Her father, Judge John Fauchereaud Grimke, was a highly conservative and strict man. Despite the family owning many slaves, he often made his children work on the plantation; picking cotton and corn were his means of discipline. Judge Grimke was also a staunch believer in traditional gender roles and, for this reason, he never formally educated his daughters. Instead, Angelina was tutored by her older sister, Sarah. Sarah had been tutored by their older brother who had attended Yale University and she passed down her knowledge to Angelina.

In 1829, Angelina followed her sister Sarah who had left in 1821 to move to Philadelphia, where both sisters converted from Episcopalianism to Quakerism. Quakers were firmly against slavery and also held more liberal views when it came to women’s rights. Both these were key philosophies of the Grimke sisters and they found the religion far more appealing than the traditionality of Episcopaliansim. Philadelphia was by no means a liberal or forward-thinking town, and in fact, Grimke witnessed the violent riots against abolitionists after she joined an anti-slavery advocacy group.

Much of why the sisters joined the abolitionist movement can be attributed to their childhood and their exposure to slavery in their home. Since Judge Grimke would often force them to work outside in the plantation, the sisters had a shred of an idea of what life was like for slaves. Of course they were not subjected to the horrors that Judge Grimke’s actual slaves were becausethey were still his children. Yet, the experience was enough for both women to condemn and fight slavery until the day they died.

The year 1835 was pivotal in the Grimke sisters’ careers as abolitionists. Another abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison, wrote and published a powerful plea to the people of Boston asking them to end mob violence. After reading the piece, Angelina decided to write him a letter. She wrote, “If persecution is the means which God has ordained for the accomplishment of this great end, emancipation, then…I feel as if I could say, let it come; for it is my deep, solemn deliberate conviction, that this is a cause worth dying for” and that “the ground upon which you stand is holy ground, never-never surrender it ... if you surrender it, the hope of the slave is extinguished.” Grimke urged Lloyd to maintain his stance on abolition and not to allow anti-abolitionists, or violence, to stop him. Lloyd found the letter quite compelling, so much so that he published it in The Liberator, an abolitionist newspaper. He published her work without asking for Grimke’s permission and, despite her embarrassment at the attention, solidified her position as a public figure.

In 1837, Angelina and Sarah became the first two women agents of the American Anti-Slavery Society. They toured New York and New Jersey, giving lectures on the cause. Despite facing gender-based criticism, the duo’s first tour was considered quite successful. Angelina especially became renowned for her commanding and captivating speaking skills, and many considered her unrivaled, even to her male counterparts. Shortly after their first tour, they went on another in the greater New England area. This tour was even larger than the first, and their audience even more diverse. For the first time, both men and women came to listen to the sisters and their influence grew rapidly.

The Grimke Sisters were repeatedly forced to defend their rights and capabilities as women. Women in the public sphere were frowned upon, especially those in politics. To be taken seriously as abolitionists, the sisters realized they had to dismantle those misogynistic beliefs.

Angelina also had a belief that was relatively unique at the time, “All moral beings have essentially the same rights and the same suits, whether they be male or female” and she iterated this idea in her piece, Appeal to Christian Women of the Southern States. The piece was addressed to the women of her hometown, Charleston. She wrote, “I know you do not make the laws,” she wrote, “but I also know that you are the wives and mothers, the sisters and daughters of those who do.” Unfortunately it did not make the impact she had wanted it to. She was threatened with imprisonment if she was ever to return to the town.

After the relative failure of Appeal to Christian Women of the Southern States, Angelina redirected her attention to a new audience: the people of the North. Letters to Catherine Beecher, which consisted of a series of letters addressed to Catherine Beecher, was a direct attack and condemnation of racism, slavery, and all those people who supported the discrimination. Beecher was quite conservative and had written an essay expressing her views of women and abolition to which Grimke countered. She wrote, “‘Much evidence,’ thou sayest, ‘can be brought to prove that the character and measures of the Abolition Society are not either peaceful or Christian in tendency, but that they are in their nature calculated to generate party spirit, denunciation, recrimination, and angry passion.’ Now I solemnly ask thee, whether the character and measures of our holy Redeemer did not produce exactly the same effects? Why did the Jews lead him to the brow of the hill, that they might cast him down headlong; why did they go about to kill him; why did they seek to lay hands on him, if the tendency of his measures was so very pacific?” Many considered Angelina an extremist because of Letters to Catherine Beecher, because even most abolitionists were not quite so outspoken and radical.

In 1838, Angelina became the first woman to speak to a legislative body in the United States when she addressed a panel of Massachusetts lawmakers on the cause of abolition.

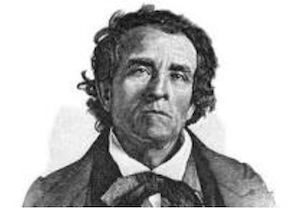

In the same year, Angelina Grimke became Angelina Grimke Weld, after marrying Theodore Weld. Similar to Angelina, Theodore was an abolitionist writer, speaker, and organizer. He was also the editor of The Emancipator. After Angelina retired, the two of them moved to New Jersey and had three kids. Along with her sister Sarah, they opened and operated two boarding schools until 1862.

In 1879, Angelina Grimke Weld passed away in Boston, after a series of strokes which left her paralyzed.

Angelina Grimke was a radical and inspiring woman. She was able to do what took the rest of the world decades, if not centuries, more to do: effectively connecting and fighting against multiple systems of oppression.

Why Did I Choose to Research Angelina Grimke Weld?

My interest in Angelina Grimke Weld came from reading Women, Class, and Race by Angela Davis. Davis’ book was centered on intersectionality between these three categorizations, and Grimke was the perfect example. Intersectionality is something that is extremely complex and I feel that many people today do not acknowledge or understand it. Yet Grimke did, decades - maybe centuries - before everyone else. She was an extraordinarily special woman.

Works Cited

Angelina Grimké weld. NATIONAL ABOLITION HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM. (n.d.). Retrieved June 18, 2022, from https://www.nationalabolitionhalloffameandmuseum.org/angelina-grimkeacute-weld.htm.

Grimke's appeal. (n.d.). Retrieved September 11, 2022, from http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/abolitn/abesaegb1t.html.

Michals, D. (2015). Angelina Grimké Weld. National Women's History Museum. Retrieved June 18, 2022, from https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/angelina-grimke-weld.

Tikkanen, A. (n.d.). Angelina Grimké. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 18, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Angelina-Grimke.

U.S. Department of the Interior. (2015, February 16). Grimke Sisters. National Parks Service. Retrieved June 18, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/grimke-sisters.htm.

This article was published on 12/12/22