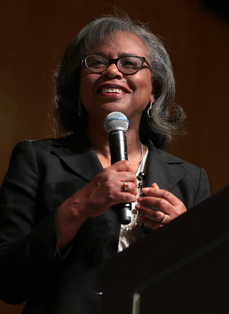

Anita Faye Hill was born and raised in rural Morris, Oklahoma, on July 30, 1956 to Albert and Irma Hill on their family farm. In 1973, Hill graduated from high school as valedictorian and a National Merit Scholar. Immediately after, she attended the University of Oklahoma to pursue her Bachelor’s Degree in psychology, which she earned in 1977. When she worked briefly as an intern for a local judge, she discovered her passion for law, and so she decided to attend Yale Law School. In 1980, she graduated from the prestigious program with a doctorate in jurisdiction.

After graduating from Yale, Hill briefly worked at Ward, Harkrader & Ross, a private law firm. In 1981, she assumed the position of legal adviser to Clarence Thomas, who was the head of the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights at the time. Although Hill was not initially vocal about the harassment she experienced under Thomas, she later explained that he began making repeated sexual advances and lude remarks during this time. Unfortunately, workplace harassment was not widely opposed in the United States during this time period. In fact, the term “sexual harassment” was first coined in 1975, and even in the 1980s, many juries and even judges were still not aware of the legal implications of this form of harassment. Women were expected to tolerate explicit sexual remarks, aggressive advances, and other forms of harassment.

Eventually, Thomas’ harassment of Hill and other women in the office ceased. When Thomas became the chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), Hill moved to that department and became his assistant. Unfortunately, Thomas soon began harassing Hill again, and she could no longer tolerate his constant inappropriate behavior. After leaving her position at the EEOC, Hill was briefly hospitalized for stress-related issues before becoming a professor at Oral Roberts University (ORU) in Tulsa, Oklahoma. At ORU, Hill taught civil rights, contracts, and commercial law. Hill worked there for several years before joining the faculty of the University of Oklahoma College of Law. In 1989, Hill became the first tenured black professor at the university and worked as the provost, where she implemented academic policies and allocated administrative resources.

Nevertheless, her past experiences with Clarence Thomas were not fully in the past. In 1991, when Thomas was being appointed to the Supreme Court, Hill was interviewed by the FBI in an investigation of his character. During this interview, Hill explained Thomas’ horrible actions and statements, but did not plan to publicly address the harassment she endured. However, her testimony to the FBI was leaked to the media, and it quickly initiated a massive discussion about Thomas’ behavior. The Senate Judiciary Committee, who was conducting hearings regarding Thomas’ appointment to the Supreme Court, decided to further investigate Hill’s accusations. They used a subpoena to obligate Hill to testify in front of the Senate and to a national audience in televised hearings. Hill confidently repeated her allegations against Thomas, but she was berated by the Senate Judiciary Committee, composed of all white men. They claimed that she was lying, exaggerating, or imagining the events she described.

When Thomas was given the chance to defend himself, he denied Hill’s allegations. The Senate disregarded Hill’s assertions, and they appointed Thomas to the Supreme Court by a vote of 52-48, the smallest margin for any of the judges on the Supreme Court at the time. Although Thomas prevailed in his Supreme Court appointment, Hill’s outspokenness had a massive national influence. Just one month after Hill’s televised accusation against Thomas, Congress passed a law to increase rights for victims of sexual assault. Moreover, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission experienced a 50% increase in sexual-harassment complaints because victims felt more valid in fighting for their personal rights. By holding Clarence Thomas accountable, Anita Hill gave a voice to countless victims of workplace harassment and affirmed the belief that women are entitled to feel safe at their jobs.

As a result of her testimony, Hill faced threats, discrimination, and massive backlash. Although she returned to her teaching position at the University of Oklahoma, she eventually resigned in 1996 due to aggression from conservative faculty. While she was hesitant to discuss her own story, Hill began speaking nationally and internationally to spread awareness about inequality, misogyny, and harassment. She wrote articles about civil rights for Newsweek and the New York Times, and in 1997, she published her autobiography, Speaking Truth to Power, about her stand against harassment. Additionally, Hill co-edited Race, Gender, and Power in America: The Legacy of the Hill-Thomas Hearings with Emma Coleman Jordan, a compilation of essays that analyze the historical context and implications of the hearings.

Despite the hate she faced for her courage and determination, Hill has continued to advocate for gender equality and civil rights. Currently, at 63 years old, she still writes articles for various news sources regarding current events. In 2018, Hill spoke out against Brett Kavanaugh, who was appointed to the Supreme Court amid rape allegations from Dr. Christine Blasey Ford. Hill enjoys remaining as private as possible, as it was never her intent to become a public figure. Yet, when she was forced into the public eye, Hill bravely opposed a behavior that was so normalized in American society. Women did not realize that harassment was illegal because they experienced it so frequently throughout their careers. Hill demonstrated that women did not have to tolerate harassment, and she started a movement for women who had been oppressed in the workplace for years. By telling her own story of repeated harassment from a man in power, Anita Hill amplified the voices of millions of other women and men struggling with workplace harassment.

Why Did I Choose to Research Anita Hill?

I researched Anita Hill because I admire Hill’s courage and impact on the modern women’s rights movement.

Works Cited

Armstrong, C. (2020). Hill, Anita F. | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Okhistory.org. Retrieved 15 June 2020, from https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=HI005.

Bennett, J. (2020). How History Changed Anita Hill. Nytimes.com. Retrieved 15 June 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/17/us/anita-hill-women-power.html.

Berenson, T. (2020). Anita Hill: TIME 100 Women of the Year. Time. Retrieved 15 June 2020, from https://time.com/5793719/anita-hill-100-women-of-the-year/.

Editors, B. (2020). Anita Hill. Biography. Retrieved 15 June 2020, from https://www.biography.com/activist/anita-hill#:~:text=Anita%20Faye%20Hill%20was%20born,as%20valedictorian%20of%20her%20class.

Hobbes, M., & Marshall, S. (2018). Anita Hill. You're Wrong About [Podcast]. Retrieved 15 June 2020, from https://www.stitcher.com/podcast/michael-hobbes/youre-wrong-about/e/54637439?autoplay=true.

This article was published on 7/28/20