Born July 6, 1997, Frida Kahlo (Frida Kahlo de Rivera) was originally named Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón. She was raised in the neighborhood of Coyocan in Mexico City, Mexico. Kahlo was raised by a German father of Hungarian descent named Wilhelm (Guillermo) Kahlo and a Mexican mother of both Spanish and Native American descent named Matilde Calderon Gonzalez. Her father was a professional photographer who immigrated to Mexico where he met and married Kahlo’s mother in 1898. Kahlo was a middle child in a family of six, with two older sisters named Matilde and Adriana and a younger sister named Cristina, who was born a year after Kahlo.

When Kahlo was six years old, she contracted a bout of polio, leaving her bedridden for nearly nine months. After she recovered from the disease, Kahlo was left with a slight limp in her right leg that she endured for the rest of her life. Kahlo was close to her father, and he encouraged her to participate in sports, such as soccer, swimming, and even wrestling to aid her recovery, and she did all three. At times, she assisted her father in his photography studio, where Kahlo acquired a sharp eye for detail the more time she spent there.

Despite taking a handful of drawing courses, Kahlo had a keen interest in science when she attended the acclaimed National Preparatory School in Mexico City in 1922 as one of few girls in her classes. She was a carefree spirit who enjoyed wearing traditional clothing and jewelry with vibrant colors. In addition, Kahlo befriended politically and intellectually intelligent individuals at the school, leading her to partake in the Young Communist League and the Mexican Communist Party. During Kahlo’s time at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City, she met the famed Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, who was painting a mural for the school’s auditorium at the time.

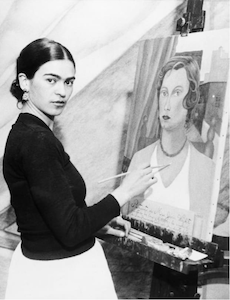

On September 17, 1925, 18-year-old Kahlo and her school friend–with whom she was romantically involved–Alejandro Gomez Arias were traveling in a bus when it collided with a street car. Kahlo was impaled by a steel handrail in the collision. This bus accident induced multiple fractures: in the spine, collarbone, ribs, pelvis, feet, and shoulders. As a result, she underwent 30 medical operations. Once Kahlo was released from the Red Cross Hospital in Mexico City, she began to paint while recovering in a body cast. As Kahlo underwent her recovery, she taught herself how to paint while studying the art of the Old Masters. This teaching led her to complete her first self-portrait in the coming year and resulted in her giving the painting to the individual who endured the bus accident by her side: Gomez Arias. That self-portrait would come to be known as the Self Portrait Wearing a Velvet Dress (1926).

After Kahlo reconnected with Rivera in 1928, she married him the following year on August 21, 1929. By 1929, Kahlo painted her second self-portrait titled Time Flies, which captures a folk style in bright colors. In addition, Kahlo changed her painting and personal style after the marriage, wearing her trademark traditional Tehuana dresses. She wore flowered headdresses, loose blouses, gold jewelry, and long ruffled skirts, which correlated to the traditional Tehuana style. Kahlo took this new attire into her artwork: Frida and Diego Rivera (1931). Kahlo painted that work alongside Rivera while traveling to the United States. This piece also demonstrated Kahlo's newfound interest in Mexican folk art and the new role she wanted to take on: a traditional Mexican wife.

From 1930 to 1933, Kahlo and Rivera lived in multiple places in the United States to accommodate Rivera’s commissions, including San Francisco, New York, and Detroit. As time progressed, Kahlo experienced multiple miscarriages. Following a miscarriage and her mother's death, Kahlo painted some of her most troubling works: Henry Ford Hospital (1932) and My Birth (1932).

Once Kahlo and Rivera returned to Mexico in 1933, the couple constructed a house. Their home became a gathering spot where artists and political activists alike could meet one another. One of those individuals was Andre Breton, a French poet and the founder of Surrealism, whom Kahlo befriended in 1937. He was responsible for Kahlo’s early recognition and proclaimed that her art was “self-made Surrealism”. Kahlo recalled, “They thought I was a Surrealist but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.” In 1938, she sold over 25 paintings at an exhibition in a New York City gallery and received two art commissions. Later in 1937, both Kahlo and Rivera began to experience periods of separation, and by 1939, Breton aided Kahlo in her first exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City. That same year, Kahlo divorced Rivera because of the affairs Rivera had with women and Kahlo’s with both men and women. After the divorce, Kahlo painted The Two Fridas (1939).The Two Fridas was a representation of Kahlo’s divorce from Rivera, which symbolized her endured heartbreak during their relationship.

Later in 1939, Kahlo moved to Paris for work showcases. There, she met more Surrealists and developed friendships with other artists, including Marcel Duchamp and Pablo Picasso. The Louvre also framed one of Kahlo’s works: The Frame (1938). By 1940, both Kahlo and Rivera reconciled to remarry and moved into her childhood home: La Casa Azul, which translates to “the Blue House.” In 1941, Kahlo received a commission from the Mexican government to paint five portraits of renowned Mexican women; however, she never completed them because she experienced the death of her father that year and began to experience chronic health problems. By 1943, Kahlo became a professor of painting at La Esmeralda: the Education Ministry’s School of Fine Arts. However, as her health declined, she sought alcohol and drugs for relief during this period.

In 1950, though Kahlo was diagnosed with gangrene in her right foot and visited the hospital perpetually for operations, she continued to paint and continued to be politically active. Then in 1953, Kahlo had her first solo exhibition in Mexico. Although she was bedridden at the time, she did not miss its opening, arriving by ambulance. She socialized throughout the event all while a four-poster bed was set up for her in the gallery. In April 1954, Kahlo was hospitalized for poor health, and she returned to the hospital two months later for bronchial pneumonia. On July 2, 1954, Kahlo made her final public appearance 11 days before her death at a protest regarding the intervention of the United States in Guatemala; her political activism continued despite her health condition. Finally, on July 13, 1954, Kahlo died in La Casa Azul one week after she turned 47.

After her death, La Casa Azul was opened as a museum in 1958. The Museo Frida Kahlo was also developed to display artifacts from Kahlo’s life and a handful of her paintings, such as Frida and Caesarean (1931), Portrait of My Father Wilhelm Kahlo (1952), and Viva la Vida (1954). During the 1970s feminist movement, interest in Kahlo’s life and work persisted, and she became an icon for female creativity.

Why Did I Choose to Research Frida Kahlo?

Growing up as a Mexican-American in Chicago, I continuously saw Frida Kahlo’s face in products from posters to phone cases. Kahlo’s continuous appearance in my life has only made me more curious about her life as well as the impact she made to be renowned and highlighted in my heritage. I had always admired her as a young Latina girl, which is why I saw myself in her growing up. Her vibrant wardrobe and captivating features interested a little girl such as me, and another one of her trademarks also mirrored one of mine: her unibrow. When another young girl pointed mine out, I was apprehensive of the idea that I even had one when the girl in front of me didn’t have two brows connected above her eyes. I thought a unibrow was a problem that I needed to fix, but as I continuously saw Kahlo, I gained much more confidence in my appearance during that period of my life.

Works Cited

Bryon, Molly. “The Two Fridas.” Encyclopædia Britannica Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., http://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Two-Fridas

Editors, Biography.com. “Frida Kahlo.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 19 Nov. 2021, https://www.biography.com/.amp/artist/frida-kahlo

“Frida and Diego.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 1 Jan. 2006, http://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/fodors/top/features/travel/destinations/mexico/mexicocity/fdrs_feat_101_9.html

“Frida Kahlo and Her Paintings.” Frida Kahlo: 100 Paintings Analysis, Biography, Quotes, & Art, https://www.fridakahlo.org/

“Frida Kahlo: Moma.” The Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/artists/2963

Magazine, Smithsonian. “Frida Kahlo.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 Nov. 2002, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/frida-kahlo-70745811/

Zelazko, Alicja. “Frida Kahlo.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 24 Mar. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Frida-Kahlo

This article was published on 3/4/24