Shidzue Katō (also known as Shidzue Ishimoto or Shidzue Hirota) is of Japanese descent and was born on March 2, 1897 in Tokyo, Japan into an ex-samurai family of great wealth. Her family consisted of herself, her father, Hirota Ritarô, who was a successful mining engineer graduating from the Tokyo Imperial University, and her mother, Tsurumi Toshiko, who had been formerly educated at a missionary school. Her parents instilled Western values into their household, especially when Japan was changing from a feudal society to a more contemporary one. Although this transformation was occurring, women still did not have equal rights as promised. Katō attended the prestigious Peeresses’ School (also known as Gakushuin Girls’ Junior and Senior High School) with other aristocratic Japanese families. The school was known to provide only major formal schooling, educating the children of the Imperial aristocracy and social elites which now encompasses preschool through tertiary-level education as prior it was believed that a woman should not be educated to such an extent. Specifically, historic Japanese beliefs were that “too much education spoils a woman’s precious virtues–obedience and naive sweetness.” Therefore, the school’s curriculum was only present to shape young women into a “good wife and a good mother” so they would obey their husbands and fulfill their role as typical housewives.

At the age of 17, Katō married Baron Keikichi Ishimoto, an Imperial university student and Christian humanist who was interested in social reforms. Katō’s life changed after her husband decided to continue his engineering degree by working in Western Japan’s Miike Coal Mining Fields because she was able to see and realize the troubles of Japan’s lower class. One day she decided to go into the mine herself to better understand the gruesome conditions the community faced. There, she witnessed countless deaths and observed how both men and women alike worked 12 to 14 hours per day half-naked in a dark, wet environment. Furthermore, it is said that pregnant women had to give birth in the mines underground and “would come up to the surface with the baby still attached by the umbilical cord.” A few days after giving birth, these women returned to the mines without pay, continuing to labour in the torture. The children would be raised by either their grandmother or a neighbour and soon after they were old enough to work, the children entered the mines to help provide for the family, leading to a never-ending cycle of poverty continuing in the households of Japan. Realizing the difficulties her people had to face, Katō longed to change the system which enforced such brutal conditions upon them. Evidently, her spark led to a global change, and this not only influenced other countries to make this change, but also helped improve individual women’s lives. She is known as the “Margaret Sanger of Japan” because of her tenacity and commitment to change the lives of the women residing in the Empire of Japan.

Katō questioned this system where managers got to live without any worries while the workers had to work to death, especially with women only receiving a subsistence pay. After witnessing the horrendous mining conditions, Katō and her husband suffered a health breakdown prompting the couple to move to the United States in 1919.

In the States, Katō got to experience what freedom felt like. During her stay in America, Katō gained a newfound confidence and independence by attending English and secretariat classes while her husband attended meetings for the International Labour Organization in Washington, D.C., serving as a consultant and interpreter. This period was crucial for Katō because she began to socialize with other socialist acquaintances of her husband, and this eventually led to her meeting with Margaret Sanger, who is the woman that gave Katō the idea to form a birth control movement in her homeland, Japan.

When Katō returned back to Japan, she continued to strive for economic independence and wanted to educate the people of Japan about birth control. Thus, she got a new job, working as a private secretary for the company, Y.W.C.A., which consisted of introducing Western visitors to Japanese culture and people. Katō also opened up a yarn shop of her own named Minerva Yarn Store where she sold imported wool products. However, an earthquake in 1923 destroyed Katō’s shop, but her influence was ever-growing in the country. She established the Women’s Research Institute, yet she was not satisfied because she was unable to offer contraceptives which she studied under Sanger. In 1932, she established the Birth Control Consultation Centre, which housed nurses and doctors as well as stored contraceptive creams and jellies. Notably, Katō was the individual managing the manufacturing and distribution of the products.

She also published many writings regarding the right to birth control, the positive impact it would have for women, and how women would be able to control the number of children they want to produce; thus, women would be able to provide better for their children in terms of economic and educational opportunities. Around this time, she met her eventual husband named Kanjū Katō who was a labour organizer and arranged a meeting for her to speak with the miners at the Ashio copper mine. In 1944, she divorced her first husband and married Kanjū. In her autobiography, she wrote that her husband, Ishimoto “had made a 180-degree conversion from his position as an intellectual humanist and a pacifist and had embraced the theory that it was natural for Japan to undertake imperialist aggression in Manchuria and Mongolia.”

In 1937, Katō was arrested by the right-wing-pro-natalist Japanese government for promoting “dangerous thoughts,” specifically for her birth control and abortion rights movements; therefore, she spent two weeks in prison. Thus, the birth control movement in Japan temporarily came to a halt and did not resume until after World War II. With the repatriation of millions of soldiers and colonists from the previous empire, the number of illegal abortions increased dramatically as did the birth rate, and the government’s and the medical profession’s opposition to birth control faded. Prewar birth control pioneers like Katō, resurfaced to help the movement realize its goals. Although Katō opposed the bill’s preference for abortion over contraception, Katō was in favour of the 1948 Eugenics Protection Law (Yûsei Hogo Hô), which made abortion legal in order to protect the health of mothers, furthering Katō’s goal of providing women with freedom to their reproductive rights.

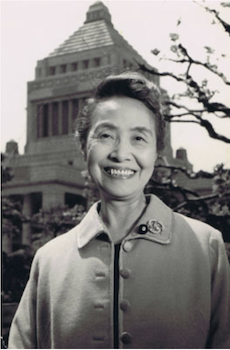

In 1946, Katō achieved another great feat by being the first woman to be elected into the Diet of Japan, thus entering the highest political decision-making organ in Japan. Her campaign specifically focused towards family planning and improving the economic prospects of women. She published the following statement in 1946 in regards to the relationship between the birth control movement and Japanese democracy:

“Giving birth to many, and letting many die—repeating such an unique way of life for Japanese women will result in exhaustion of the maternal body, as well as mental damage and material loss for the family… Without the liberation and improvement of women, it is impossible to build democracy in Japan.”

Later she was also elected to four six-year terms in the Upper House where she continued to advocate for women’s rights and family planning, specifically she championed for birth control legislation, the abolition of the feudal family code, the establishment of the Women’s and Minors Bureau of the Department of Labour, as well as environmental issues. Moreover, she also helped establish the Family Planning Federation of Japan which strives to achieve “a society where everyone in the country can have access to voluntary reproductive health services.” One of Katō's publications is Facing Two Ways: The Story of My Life which is an autobiography of her life and journey, republished by the Stanford University Press in 1984. In an interview from 1985, Katō expressed that the biggest motivations in her journey were the Miike Coal Mine discovery and her meeting with Sanger in 1920.

Katō never stopped her political activism and continued to lecture society on feminist issues, continuing her chair at the Family Planning Federation of Japan. One of her greatest accomplishments was receiving the United Nations Population Award in 1988—a fund given to recipients who have made significant contributions in the field populations and reproductive health issues. Additionally, recognized for her heroic work, The Katō Shidzue Award, established by Dr. Attiya Inayatullah, was created to commemorate her great work. It is said that The Katō Shiduze Award “targets women’s groups, women’s organization and/or individual women who are active in the movement toward improvement of sexual and reproductive health/rights of women as well as empowerment of women (i.e., social, economic, political and legal empowerment) in developing countries and/or in Japan.”

Katō died on December 22, 2001 at the age of 104, beside her family due to respiratory failure, having lived through three centuries. An obituary on Katō published by the International Planned Parenthood Federation praised how Katō’s efforts “have continued to bear fruits for Japanese society, bringing down the number of abortions, infant mortality, and maternal death rates, while increasing contraceptive usage to 80 percent. Japan’s family planning model has been so successful that it attracts attention from other countries as a working model”, all thanks to the pioneer of the birth control movement, Shidzue Katō.

Why Did I Choose to Research Shidzue Katō?

As a passionate admirer of Japanese customs, I wanted to research a woman of Japanese background and Shidzue Katō immediately caught my eye as she was the first woman to be elected into the Diet of Japan, sparking a great change in Japanese history. She, in particular, is a role model to today’s society as she exemplifies the belief that any woman is able to bring a great change in society. In addition, I also enjoy learning about Japan’s history, culture and traditions!

Works Cited

Hernon, M. (2021, December 22). Spotlight: Shidzue Kato — Pioneer of Japan’s Birth Control Movement. Tokyo Weekender. https://www.tokyoweekender.com/art_and_culture/spotlight-shidzue-kato/

Johnson, M. S. (1987). Margaret Sanger and the birth control movement in Japan, 1921-1955. UMI. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/5420be9c-a696-41c1-bca9-b242afff7004/content

Kato, Shidzue 1897-2001 | Encyclopedia.com. (n.d.). Www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved April 30, 2024, from https://www.encyclopedia.com/arts/educational-magazines/kato-shidzue-1897-2001

Molony, B. (1997). [Review of A New Woman of Japan: A Political Biography of Katō Shidzue, by H. M. Hopper]. The Journal of Japanese Studies, 23(1), 183–186. https://doi.org/10.2307/133138

【懐かしい出会い】マーガレット・サンガー夫人の功罪 - 六文錢の部屋へようこそ!. (2020). Goo Blog. https://blog.goo.ne.jp/rokumonsendesu/e/3dca43d6b315bee5e875a170aef84f65

Ryoichi, S. (2016, June 13). 加藤シヅエさんの言葉・人となり | インタビュー&ストーリー. 国際協力NGOジョイセフ(JOICFP). https://www.joicfp.or.jp/jpn/2016/06/13/33710/

Tipton, E. K. (1997). Ishimoto Shizue: The Margaret Sanger of Japan. Women’s History Review, 6(3), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/09612029700200151

This article was published on 9/23/24