Susanne Knauth Langer was born on December 20, 1895 in New York City to well-off German immigrants Antonio and Else Knauth. She grew up with two sisters and two brothers. As a family, the Knauths dedicated themselves to music. Langer kept a beloved cello in a glass case inside her family’s home, and it traveled with her even when she went to college and moved to Connecticut. This expertise in the musical world later gave her a new perspective when studying philosophy and aesthetics in college. Along with playing music, as a child, Langer would wander on hiking trails, inspiring her nickname “forest witch.” Unfortunately, this adventurous spirit ceased (at least physically) when young Langer got cocaine poisoning from a pharmaceutical error. Sickly and confined to her home for a few years, she was tutored extensively and was able to intellectually explore outside of the boundaries of a classroom. Those who knew her stated that she loved reading and ravenously consumed difficult works of philosophy even at a young age.

After her recovery, Langer began attending the French-speaking Veltin School in Manhattan. This French education, combined with her German-speaking household and English-filled college experiences, led to proficiency in all three languages. Fellow philosophers have theorized that her trilingual childhood gave her a greater depth of experience when she later began teaching and writing on expression and emotion. During this time, Langer hadn’t applied to college, much less decided to become a philosophy teacher. In fact, her father didn’t even want her to go to university, but her mother encouraged her to apply to Radcliffe College. She was accepted and began attending in 1916.

Langer thrived at Radcliffe. Under the tutelage of Alfred North Whitehead, celebrated process philosopher, she graduated in 1920 with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy and decided to continue her education at Harvard University. There, she met William L. Langer, a future Harvard professor and historian. They married in 1921 and took a year-long honeymoon in Austria, where Susanne continued her philosophy degree at the University of Vienna. After returning to the United States, she finished her master’s degree in philosophy and attended an additional two years at Harvard to obtain a doctorate. She remained in academia and began to work as a philosophy tutor at Radcliffe. She also translated several philosophy works from the famed German philosopher Ernst Cassirer. The Langers and their two sons lived together in Cambridge, Massachusetts until William and Langer divorced in 1942.

The same year, Langer quit her tutoring position and subsequently released her celebrated book Philosophy In A New Key. Though her first book was a simple collection of fairy tales released in 1924, and her early research involved analytic philosophy, she found her niche in aesthetics (principles associated with nature, beauty, and art). Her college mentor Alfred Whitehead and his theory of symbolic reference had much influence on her own theories; Whitehead wrote extensively on the idea that “symbols” found in human experience could evoke certain “meanings”. Symbolic reference was the process of the mind transferring between symbols and meanings. Combining these more scientific and psychological ideas with her artistic upbringing, Langer theorized that art was almost a kind of symbol that evoked meanings that no language or writing could inspire. Arguing that art was a high form of expression that could portray the nature of feeling itself while language could not, she challenged the dominant assumptions in the fields of aesthetics and linguistic analysis. Her basic thesis was that when an artist creates a work, they portray the nature of feeling itself rather than simply trying to arouse feeling with the piece. Published by Harvard University Press, Philosophy In A New Key sold around 500,000 copies and remains one of Harvard’s all-time bestsellers. The work turned Langer into one of the most widely read philosophers of her time, and the book commonly appeared on college syllabi for a wide range of courses. A fellow professor once said, “When I was a student, everyone had at least one dog-eared copy of Mrs. Langer’s….it seemed to be assigned reading for half the courses in the College.” Though the book is not often cited by today’s philosophers due to the advent of postmodernism and its rejection of previous theories, her ideas have nevertheless become fundamentally integrated into society’s mindset around art and music.

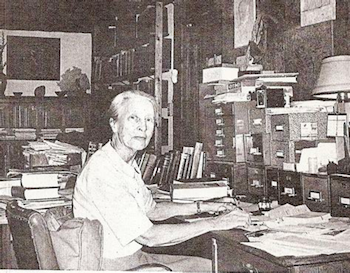

After her success with Philosophy In A New Key, Langer began to lecture at Columbia University in 1945 before becoming a professor at Connecticut College in 1954. There, she was the chair of the philosophy department until she received a research grant from the Edgar Kaufmann Charitable Trust of Pittsburgh. Following this grant, she was able to dedicate her time to writing in a small secluded home in Ulster, New York. Along with writing, she spent her time doing occasional guest lectures at colleges such as NYU and Northwestern, taking care of many small pets, and playing her cello. She began work on her three volumes of Mind: An Essay On Human Feeling; the series would be the result of the rest of her life’s work and her magnus opus. Her goal was to trace the origin and development of the mind, and connect current human intellect and emotion as evolving from more base animal instincts. She began by expanding on ideas in aesthetics such as why vitality is found in organic forms, before extrapolating her conclusions to many different fields from biochemistry to ethology. In an interview with the New York Times, Langer said she was “trying to develop basic concepts which underlie all…fields of study, and which can rule all such thought.” She seems to have somewhat succeeded: while Mind was not the influential masterpiece she expected it to be and she was forced to stop writing due to blindness soon before her death, the earlier Philosophy In A New Key has been incredibly influential, even now being cited by those in a wide variety of professions: art scholars, urban planners, inventors, anthropologists, psychologists, et cetera. She also had incredible influence in her own field - she is heavily referenced in the classic compilation A Modern Book of Esthetics by Melvin Radar, which is regarded as the ultimate book on aesthetic philosophy and is a standard in college philosophy curricula.

Her work as one of few women of the time based in academic philosophy was rightfully recognized. In 1960 she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a group which honors excellence and leadership. As one of the oldest learning societies in the United States, created during the revolution by Founding Fathers, membership into the society is an honor. Langer died peacefully in her home in Old Lyme Connecticut on July 17, 1985. Three years later, a bronze statue of her was dedicated at Connecticut College, where her papers are stored and can be viewed. She remains one of the most prominent female philosophers, even as her work and contributions unfortunately begin to be forgotten.

Why Did I Choose to Research Susanne Langer?

I was learning about Aristotle and other classical philosophers for a European history class, and I began to wonder why I had never heard of a single female philosopher. After doing some research on women in the field, I became especially interested in Susanne Langer due to her theories on artistic expression and my own hobbies of painting and drawing. She seemed the perfect fit for an iFeminist article due to her fascinating and important work as well as her relative obscurity.

Works Cited

(n.d.). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved August 19, 2022, from https://www.amacad.org/.

Amadio, A. H. (2022, July 13). Susanne K. Langer | American philosopher and educator. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 19, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Susanne-K-Langer.

Cassirer, E. (2020, January 13). Susanne Langer. New World Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 19, 2022, from https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Susanne_Langer.

Editors of New World Encyclopedia. (2020, January 13). Susanne Langer. New World Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Susanne_Langer.

Greer, W. R. (1985, July 19). SUSANNE K. LANGER, PHILOSOPHER, IS DEAD AT 89. The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/1985/07/19/nyregion/susanne-k-langer-philosopher-is-dead-at-89.html.

Klauber, L. (2021, March 17). Former Professor Suzanne Langer’s Legacy Lives On. The College Voice. Retrieved August 19, 2022, from https://thecollegevoice.org/2021/03/17/former-professor-suzanne-langers-legacy-lives-on/.

Lord, J. (1968, May 26). A Lady Seeking Answers. New York Times, 98, 102, 129.

Susanne Langer — CT Women's Hall of Fame. (n.d.). Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame. Retrieved August 19, 2022, from https://www.cwhf.org/inductees/susanne-langer.

Sparshott, F. E. (1968). [Review of Mind: An Essay on Human Feeling, by S. K. Langer]. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 2(3), 135–137. https://doi.org/10.2307/3331334.

This article was published on 3/20/23