Charlotte E. Ray was born on January 13, 1850, in New York, New York. She was born into a family of six siblings, with three boys and three girls. Her father, Reverend Charles Bennet Ray, was a minister and an outspoken abolitionist. Consequently, his devotion to civil rights and equality helped mold her commitment and dedication to providing justice for all people. In addition to his work in the church, he was an editor of The Colored American, one of the first newspapers published by and for African Americans in the United States. Her mother, Charlotte Augusta Burroughs Ray, valued her childrens’ education. She gave Ray and her siblings a healthy and structured home life by staying home with them while Charles was at work. Additionally, she ensured that her daughters were enrolled in school and were pushed academically. Ray lived with her family in New York City until she left for high school.

Ray began high school at Myrtilla Miner’s Institution for the Education of Colored Youth (now known as the University of the District of Columbia) in Washington, D.C., seeing as this was one of the few schools in the country that educated African-American girls. The school played a vital part in equipping Ray with the foundational knowledge and life skills that would help her advance in her entrance into the legal profession; Ray graduated in 1869 and began her studies at Howard University that same year.

She initially enrolled in the Normal and Preparatory Department, planning to become a teacher. However, Ray’s commitment to justice and civil rights led to a decision to take a different route shortly after arriving at Howard. Howard was adamant about not discriminating on the basis of gender or race, so she was admitted into the brand-new Howard School of Law. Soon Ray dropped her dream to be a teacher, and instead decided to pursue a career in law. She was still a teaching aid for a professor at the school during the day to help cover her tuition, but she would study law at night. Notably, she balanced teaching during the day with attending her classes in the evenings. On top of the academic rigor, she had to figure out how to navigate what had always been an environment dominated by white men. On February 27, 1872, Ray graduated from Howard with a law degree, making her Howard’s first female graduate. She specialized in corporate law and has been recognized as the woman mentioned by General O. O. Howard, the founder and first president of Howard University, as having “read us a thesis on corporations, not copied from the books but from her brain, a clear incisive analysis of one of the most delicate legal questions.

Women in the 19th century had been forbidden across the country from the legal profession. For example, they were kept from acquiring licenses to practice law and they could not be a part of professional settings that would allow them to advance career-wise. However, this did not stop pioneering women such as Ray. She challenged the set-in-place patriarchal paradigm by pushing ahead even when it was uncomfortable or unheard of. Therefore, she showed that she was capable and determined.

There had never been a female member of the bar of the District of Columbia, but Ray forged ahead anyway, knowing she could be the first. She took her exams as “C. E. Ray,” realizing that if she disclosed she was a woman she would not be able to pass. Subsequently, she was admitted to the bar, becoming the first female member of the District of Columbia bar. Her acceptance to the bar was not only a huge personal achievement but also a great leap for people of color and women in law. Ray’s appointment was accordingly highlighted in the Woman’s Journal and earned her inclusion as one of their Women of the Century.

In 1872, Ray started a law practice that specialized in commercial law, an area of law focused on selling and distributing goods and financing transactions. In addition to this, she took on cases handling real estate and family law. Ray’s most well-known case was her representation of Martha Gadley. Gadley was an African-American woman who had appealed for divorce from her abusive husband. Her petition was rejected in 1875. However, Ray would not give up and agreed to take the case to the District of Columbia’s Supreme Court. She successfully overturned the ruling of the lower, local courts by contending that Gadley’s husband’s routine drunkenness and violence endangered his wife, therefore making her entitled to a divorce. As a result, Gadley was able to legally separate from her husband, providing her with a sense of independence and legal protection. The win also validated Ray’s practice, earning her respect in the legal community.

Ray was forced to close her practice in 1879, despite being highly qualified and having a vast expanse of legal knowledge. Due to racial and gender prejudices, she was unable to attain a sufficient amount of legal business to maintain a consistent practice. One Wisconsin lawyer, Kate Kane Rossi, remarked in 1879 that, “Miss Ray… although a lawyer of decided ability, on account of prejudice was not able to attain sufficient legal business and had to give up active practice.” Ray’s overall success in her legal practice led to the creation of two annual awards given in her name: The Annual Charlotte E. Ray Award from the Greater Washington Area Chapter of the Women Lawyers Division of the National Bar Association and the MCCA Charlotte E. Ray Award. These accolades are given to a female lawyer for exceptional achievements in the legal profession and extraordinary contributions to the advancement of women in the profession.

Ray moved to New York City shortly after closing her law firm, where she became a teacher at a public school in Brooklyn. Ray did not stop her fight for equality, remaining an outspoken advocate for both women’s suffrage and equality for black women. She attended the National Woman Suffrage Association‘s (NWSA) yearly convention in New York City in 1876. She joined the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1895.

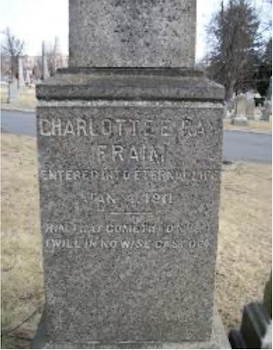

Little is known of Ray’s life after her career. Shortly after moving to New York in the 1880s, she married a man with the last name of Fraim. In 1897, she moved, accompanied by her husband to Woodside, Long Island. She had no children. Here, she passed away due to a severe case of bronchitis at the age of sixty on January 4, 1911.

Ray’s legacy lives on as a trailblazing woman of law, who brazenly made room for other women to come into the legal profession. She was willing to take the first integral steps that opened the door for a new generation to stand up and find their voices. Her fearlessness in fighting for justice and equality has been an inspiration to many women long after her death. Ray is an example for all pioneering women to never give up, even when it is uncomfortable, or you are made to feel like you do not belong. What may have been perceived as failure by many was actually the opening of a new door for women to come in and find their place in the legal profession.

Why Did I Choose to Research Charlotte E. Ray?

Ray’s legacy lives on as a trailblazing woman of law, who brazenly made room for other women to come into the legal profession. She was willing to take the first integral steps that opened the door for a new generation to stand up and find their voices. Her fearlessness in fighting for justice and equality has been an inspiration to many women long after her death. Ray is an example for all pioneering women to never give up, even when it is uncomfortable, or you are made to feel like you do not belong. What may have been perceived as failure by many was actually the opening of a new door for women to come in and find their place in the legal profession.

Works Cited

A&E Television Networks. (n.d.). Charlotte E. Ray’s brief but historic career as the first U.S. black woman attorney. History.com. https://www.history.com/news/charlotte-e-ray-first-black-woman-attorney

Association, N. D. A. (2024a, February 8). A Trailblazer in justice: The pioneering journey of charlotte E. ray. Medium. https://ndaajustice.medium.com/a-trailblazer-in-justice-the-pioneering-journey-of-charlotte-e-ray-381ba97f931c

Darling, T. (2024a, May 27). Charlotte E. Ray (1850-1911). https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/ray-charlotte-e-1850-1911/

Henrietta Green Regulus Ray. The Fight for Black Mobility: Traveling to Mid-Century Conventions. (2021, February 25). https://coloredconventions.org/black-mobility/associated-women/henrietta-green-regulus-ray/

Pinedo, J. (2022, January 31). WR immigration celebrates Charlotte E. Ray – America’s first black woman attorney. WR Immigration. https://wolfsdorf.com/wr-immigration-celebrates-charlotte-e-ray-americas-first-black-woman-attorney/

Thao. (2013, February 6). Charlotte Ray. History of American Women. https://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2013/02/charlotte-ray.html

This article was published on 10/4/24