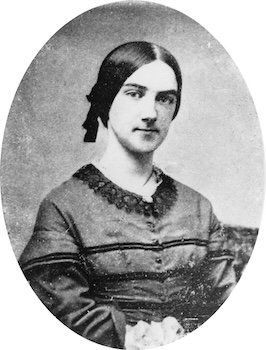

Born on December 3, 1842, Ellen Swallow Richards became one of the leading figures of her era and was the first of many pioneering women to experiment in new fields of science. She was born and raised an only child on a small family farm in the rural town of Dunstable, Massachusetts, where, following her successes, the Swallow Union Elementary School was named in her honor. She was brought up and home-schooled until high school by her well-educated and established parents, Peter Swallow and Fanny Gould Taylor, both professors who believed that their intellectually curious daughter would thrive outside of the formal education system. Richards’ relationship with her parents was one of respect and encouragement as they instilled in her a love for learning and provided her with the resources and guidance necessary to succeed.

Diagnosed with several deficiencies, including chronic fatigue, dietary struggles, and a weak heart at a young age, Richards was encouraged to spend as much time as possible outdoors, where she quickly became interested in the dynamics and interactions between humans and the environment. Furthermore, in the 1800s, women were often responsible for managing the household, which included cooking, cleaning, and ensuring the well-being of family members. Ellen Swallow Richards, despite her health issues, was no exception. These responsibilities required her to pay close attention to hygiene, nutrition, and the overall environment within the home as she took note of the importance of sanitation and its impact on health.

By 1859, Richards and her family moved to Westford, an adjacent town, where, at 17, she began at Westford Academy. Her interests and strengths spanned a variety of subjects, from mathematics and sciences to languages. Outside of school, she would work alongside her father at his store, tend to her sick mother, tutor peers, and still find time to further her own studies. By the time she graduated, staying in the STEM field as a woman of her era was quite out of reach, putting her on the teaching path following her parents. Nonetheless, when Vassar College for Women New York opened a highly selective and unprecedented program of science studies for women, Ellen jumped at the opportunity and was admitted as a third-year student after her excellent performance in the entrance exam. With a stellar recommendation from her chemistry professor, Charles Farrar, who was a firm believer in science being an instrumental tool in the community and home settings, and motivation from Maria Mitchell, an activist for women in science fields, Richards was the first woman to be accepted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1871. Though she was exempt from paying tuition, the university designated her as a “special student” to discreetly accommodate her enrollment. This status served as a way to obscure and potentially deny the formal admission of a woman if the experiment did not succeed. In 1873, Richards graduated from MIT with a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry, making her the school’s first female graduate. However, despite hiring her as a laboratory assistant and unpaid chemistry lecturer soon after, and later promoting her to instructor and laboratory head, the institution never granted her a doctoral degree.

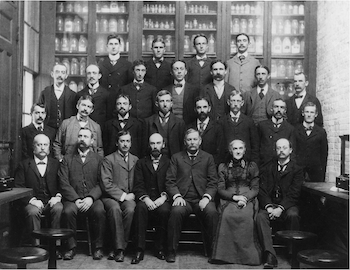

Two years later, she married Robert H. Richards, head of MIT’s Mine Engineering Department and partner in the institute’s mineralogy laboratory. Alongside her husband, she donated $1,000 every year to the “Woman’s Laboratory” at MIT, an initiative she started that was designed to train those who wanted to perform chemical experiments and explore petrology.

In addition, Richards became a teacher at the Lawrence Experiment Station, which was the first in the United States led by her former professor. Richards also used her expertise to work as a chemistry consultant for the Massachusetts State Board of Health from 1872 to 1875, the official water analyst of the state of Massachusetts for 10 consecutive years, and even as a nutrition expert for the US Department of Agriculture.

Ellen Swallow-Richards noticed the influence of resource extraction on the environment as early as the end of the nineteenth century, at the heart of the Industrial Revolution. As a result, she began studying more than 100,000 water and sewage samples from the state of Massachusetts and not only developed the “Richards Normal Chlorine Map,” used to predict the inland water pollution of the state, but also the first water purity tables.

Alongside Marion Talbot, Richards’ mentee at MIT, she became the founder of the American Association of University Women (AAUW), whose female-run board of directors pushed for an organization of women college graduates who, together, would create opportunities of higher education and training for other females. In 1881, she published The Chemistry of Cooking and Cleaning: A Manual for House-keepers, where she showcased her discoveries in home economics, ranging from nutrition and clothing to physical fitness, sanitation, and efficient home management.

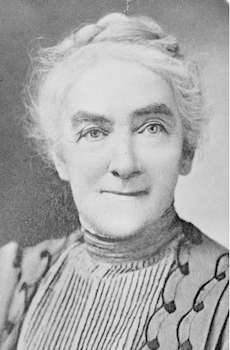

On March 30, 1911, Ellen Swallow Richards passed away in her Massachusetts home due to angina, a symptom of coronary heart disease. However, her legacy still lives on, as in 1993, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame and was honored in Boston’s Women Heritage Trail.

In 1925, her alma mater, Vassar College, established an interdisciplinary curriculum in euthenics studies, inspired by her pioneering ideas on improving human efficiency and well-being through enhanced living conditions. This initiative not only recognized Richards' contributions but also set a precedent for future generations of women in STEM. On the 100th anniversary of her graduation, MIT honored her legacy by creating the Ellen Swallow Richards Professorship, dedicated to exemplary female faculty members, reflecting her role as a trailblazer for women in science and engineering. Richards' work laid the groundwork for future female scientists, encouraging them to pursue their passions and break barriers in fields traditionally dominated by men.

Why Did I Choose to Research Ellen Swallow Richards?

As a high school student who hopes to one day attend a prominent university while staying true to her interests and not molding herself to fit expectations, Ellen Swallow Richards is an exemplary figure. What inspires me the most about the chemist is not the fact that she was the first woman to attend such a prestigious institution but her dedication to her studies and commitment to improving public health and environmental conditions, particularly through her pioneering work in sanitary science and home economics. Often, teenagers are led to believe that getting into college is the end goal, but as Richards proved, it is what you do with the opportunities given to you that matters most. Her efforts evidently shone through as she received recognition after recognition and was placed in positions of power in different departments of the state and nation, yet she never ceased to provide the foundational education and experiences for curious women to thrive as she did.

Works Cited

Balasa, J. (2022, July 8). Life story: Ellen Swallow Richards. Women & the American Story. Retrieved July 31, 2022, from https://wams.nyhistory.org/modernizing-america/modern-womanhood/ellen-swallow-richards/

Dyball, R., & Carlsson, L. (2017). Ellen Swallow Richards: Mother of Human Ecology? Human Ecology Review. Retrieved from https://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n4068/pdf/article03.pdf

Ellen Swallow Richards '1870. Vassar Encyclopedia. (2005). Retrieved July 31, 2022, from https://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/distinguished-alumni/ellen-swallow-richards/

Philippy, D. (2021, June 29). Ellen Richards's Home Economics Movement and the birth of the economics of Consumption: Journal of the history of economic thought. Cambridge Core. Retrieved July 31, 2022, from https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-the-history-of-economic-thought/article/ellen-richardss-home-economics-movement-and-the-birth-of-the-economics-of-consumption/59F5DF4FCB70A362734A8E9890CE2E28

Scene at MIT: Ellen Swallow Richards leads the Women's Laboratory. MIT News. (2017, March 21). Retrieved July 31, 2022, from https://news.mit.edu/2017/scene-at-mit-ellen-swallow-richards-womens-laboratory-0321

This article was published on 8/9/24