Sister Rosetta Tharpe, born Rosetta Nubin, was an early pioneer of Rock n’ Roll music. She influenced world-renowned rock-and-roll musicians such as Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, and Elvis Presley. Historically, she has received little recognition for the role she played in the genre’s popularization; however, recently she has gained well-earned recognition for her inspiring accomplishments and revolutionary career as a black queer woman in the mid 20th century.

Rosetta Nubin was born in Cotton Plant, Arkansas on March 20, 1915. She was the only child of laborer Willis Atkins, and singer, mandolin player, and evangelist, Katie Harper Atkins. Nubin first displayed her musical talents at a remarkably young age; by age four she was singing and playing guitar at a level unheard of for someone so young. There is no evidence of any formal education she received, if any; it is believed that the basis of her music education was from her church. At six, she, along with her mother, was part of an Evangelist troup that traveled throughout the South performing at various venues. By the 1920s, she and her mother were settled in Southside Chicago, where they joined the Fortieth Street Church of God in Christ (COGIC). It was here where her musical talents truly began to shine with the help from her mother, who was a gifted mandolin player. In her late teens, Tharpe developed her sound heralded from jazz and blues sounds she heard in Chicago mixed with gospel songs, and was traveling across the country performing for crowds of people. While she did have a large audience who loved her music, some people in the gospel community were startled with her blending of secular and religious themes, and many also disapproved of her open lyrical expression of love and sexuality.

In 1934, at age 19, Nubin married a COGIC preacher named Thomas J. Tharpe. The couple was married for only four years until 1938, and once they separated due to his philandering, Nubin moved to New York with her mother, keeping his last name as her stage name. Shortly after moving to New York, Tharpe joined the Cotton Revue Club, which had become popular during Prohibition. Here, she performed her music for a predominantly white audience that was drawn to her music and “hymn-swinging, guitar-slinging” style (Wald). This newfound popularity among white audiences also drew the attention of several record labels. Tharpe ended up signing with Decca records in 1938, making her the first ever gospel performer to record for a major record label. Shortly after, she released her first single, “Rock Me”, which was a version of the gospel song “Hide Me in Thy Bosom.” She frequently played at tent revivals, and while there aren't any clips from those, her Decca records from the early 1940s of songs like “The Lonesome Road” and “That’s All” give us a good idea of what songs she may have played at these. In 1941, she joined Lucky Millinder’s swing band, a popular rhythm and blues band, and toured with them throughout the early 1940s. During this time, her position as the frontman earned her an audience of young swing fans, and she was also popular among World War 2 soldiers, being one of two black gospel acts to record “V-Discs'' for overseas troops (McNeil, Buckalew). However, the peak of her career wasn’t until she left the band and started her solo career.

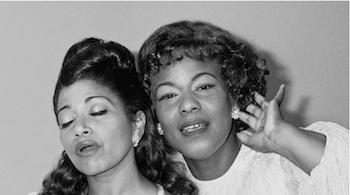

Throughout her solo career, she was accompanied by a trio including Texan pianist Sammy Price. Price and his trio were featured on her 1944 recording of “Strange Things Happening Every Day” which was the first gospel song to reach the top 10 in Billboard’s rhythm and blue records chart. Many scholars view this as the very first rock-and-roll song and have deemed her the “Godmother of Rock and Roll” (Wallenfeldt). This song especially resonated with the American public at the time as the title was an ode to the strange things happening during this time such as World War 2, the atomic bomb, and Jackie Robinson becoming the first African American to play major league baseball. In the late 1940s, Tharpe turned back to gospel music, partnering with popular gospel singer Marie Knight. By this point, Tharpe had no children and had been married to two different men, but it was known that she also had relationships with women. The chemistry that Tharpe and Knight displayed in their duets led many to believe that they were together in some form. The duo performed more religious songs such as “Didn’t It Rain” (1947) and “Up Above My Head” (1947). Tharpe’s decision to release simple blues singles caused many of her fans to become disinterested and her popularity declined significantly in the US. In 1950, after largely failing to enter the blues music scene, Tharpe and Knight stopped performing together.

On July 3, 1951, Tharpe's third and final marriage to her manager Russell Morrison took place at a concert at DC’s Griffith Stadium. 25,000 people attended and the concert was recorded to later be released as an album. Shortly after this stunt, her career began winding down and young white men began to take over the rock music scene. After losing her Decca contract and signing with Mercury records in the late 1950s, she began an international tour. Tharpe was popular among British teens who were familiar with rock-and-roll music, and she reached as much popularity there as she had in the States. In fact, she had one of her most iconic performances in Europe in 1964, in which she sang to a crowd across a trans station platform in Manchester, England. In 1970, Tharpe experienced a stroke that caused her to have a leg amputated and speech difficulties. Despite all this, she continued performing until she died due to a stroke in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on October 9, 1973.

Today, Tharpe is celebrated as a model musician and a prime example of strength, independence, and brilliance. Her story inspires women and shows them you don’t have to be a man to be a successful and well-respected musician. Her four decade career was rooted in her confidence and uniqueness in her performances, and she single handedly introduced gospel into the general public sphere. Although her accomplishments were long overlooked, she has recently begun to get the recognition she deserves. For example, she was the subject of the 2011 film The Godmother of Rock and Roll, inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame in 2013, portrayed by musician Yola in Elvis (2022), and in October of 2023 she was listed as six on Rolling Stone’s 250 greatest guitarists of all time. Most importantly, she was inducted into the rock-and-roll hall of fame under the “early influence” category in 2018, finally receiving true recognition for the profound impact she had on rock-and-roll music.

Why Did I Choose to Research Sister Rosetta Tharpe?

I chose to research Sister Rosetta Tharpe because I heard her song “Strange Things Happening Every Day” on the radio and was fascinated by her unique sound. I had never before heard the name Rosetta Tharpe and was shocked to learn how much she contributed to the rock n’ roll music scene. As someone who loves rock n’ roll music and is a musician myself, hearing her story inspired me to continue pushing myself to my best in my musical career. Her story is important for all women to know as her accomplishments were truly revolutionary, and are a testament to the heights we can reach. I think it is important for more people to learn about her frequently overlooked contributions to kickstarting the rock n’ roll music scene.

Works Cited

Diaz-Hurtado, Jessica. “Forebears: Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the Godmother of Rock ‘n’ Roll.” NPR, 24 Aug. 2017, http://www.npr.org/2017/08/24/544226085/forebears-sister-rosetta-tharpe-the-godmother-of-rock-n-roll

Gibson. Guitar.Com, 25 Feb. 2022, http://guitar.com/news/music-news/watch-gibson-drops-mini-documentary-godmother-of-rock-

McNeil, William, and Terry Buckalew. “‘sister Rosetta’ Tharpe (1915–1973).” Encyclopedia of Arkansas, 23 Apr. 2024, http://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/sister-rosetta-tharpe-1781/

Ochs, Michael. Udiscovermusic, http://www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/sister-rosetta-tharpe-rocknroll-pioneer/

Rogac, Jody. The New Yorker, 16 Aug. 2016, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/09/05/sister-rosetta-tharpe-the-first-gospel-recordin

“Sister Rosetta Tharpe.” Soulwalking, http://www.soulwalking.co.uk/Sister%20Rosetta%20Tharpe.html

Wald, Gayle. “Sister Rosetta Tharpe.” Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, http://rockhall.com/inductees/sister-rosetta-tharpe/

Wallenfeldt, Jeff. “Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 22 July 2024, http://www.britannica.com/topic/Rock-and-Roll-Hall-of-Fame-and-Museum

This article was published on 8/23/24