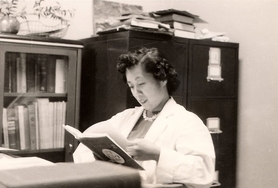

Dr. Irene Ayako Uchida was a pioneer in Canadian genetics and cytogenetics during the latter half of the 20th century. She was born on April 8th, 1917, in Vancouver, Canada to first-generation Japanese immigrants Sentaro and Shizuko Uchida. Uchida grew up in Hastings-Sunrise, a working-class neighborhood in Vancouver. Her parents owned two bookstores, which likely contributed to her lifelong love of literature. Uchida grew up playing the piano, organ, and violin, and she often performed for her local church. After the death of her best friend in a car crash and the loss of her sister to tuberculosis, Uchida became determined to help people avoid that fate.

After high school, Uchida attended the University of British Columbia to study English literature. During her time at UBC, she participated in advocacy work for the rights of Japanese Canadians through volunteering with the Japanese Canadian Citizens League and writing for their newspaper, the ‘New Canadian Newspaper.’ After her first two years at UBC, she took a break from her studies to visit family in Japan.

In November 1941, she arrived home in Vancouver on the last ship to depart from Yokohama, Japan a month before the attack on Pearl Harbour. When Uchida returned, her family, along with 22,000 other Japanese Canadians, were forcibly interned by the federal government. She was first sent to the Christina Lake internment camp, located in British Columbia’s Kootenay region. Then, in 1942, Uchida and her family were moved to the Lemon Creek internment camp. She then started a school for interned children where she served as a principal and teacher at the school until 1944. Uchida was passionate and committed to helping as many of her students as possible. In one instance, she converted her living quarters into a library where students were welcome to study.

After the war, Uchida decided to remain in Canada, even though most of her family had returned to Japan and in spite of prevalent anti-Japanese racism. However, she was forced to relocate to Toronto, as the Canadian government declared that all Japanese Canadians were to move east of the Rocky Mountains or to Japan. At the time, Toronto was closed to all Japanese Canadians with the exception of students at the University of Toronto. With the United Church of Canada’s financial support and lodging, she continued her education at the University of Toronto. She graduated in 1946 with a BA in English literature. Upon graduation, Uchida originally planned to pursue a master’s degree in social work. However, Uchida’s genetics professor Dr. Norma Ford Walker encouraged her to continue her studies in genetics and zoology. In 1951, she graduated with a Ph.D. in Zoology from the University of Toronto.

Dr. Uchida began her career as a research associate at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children, developing one of the largest twin registries in North America. She used this database to research the genetic disorders of twins with heart disease.

In 1959, she obtained a Rockefeller Grant to study at the University of Wisconsin. Initially, the United States government denied her entry as border officials considered her Japanese (despite her Canadian citizenship), and the Japanese entry quota had already been exceeded that year. With assistance from the university’s president, she obtained a special pass. Her research in Wisconsin focused on the chromosomes of fruit flies. After exposing fruit flies to cobalt radiation, she discovered that their offspring had additional chromosomes and an abnormal physical appearance.

In 1960, Dr. Uchida was hired as the director of medical genetics at the Children’s Hospital in Winnipeg, Manitoba. There, she developed a test for trisomy-18 (Edwards syndrome), which was the first diagnostic blood test in Canada to karyotype an infant’s chromosomes. Dr. Uchida’s method of chromosomal testing was later used to test amniotic fluid for chromosomal abnormalities in a fetus. The development of this diagnostic blood test marked the founding of Canada’s first clinical cytogenetics program. Cytogenetics focuses on the study of chromosomes and how changes in their structure and number can cause disease.

Two years later, she published case studies of trisomy-18. Her most notable accomplishment was studying the link between radiation exposure in pregnant women and the prevalence of Down syndrome in their babies. By conducting investigative interviews with parents, Dr. Uchida proved the prevalence of Down syndrome in people who had been exposed to X-rays while in utero. Her studies also proved that the trisomy that causes Down syndrome could be inherited from either parent, when it was previously thought that it could only be inherited from the mother. Dr. Uchida was also a pioneer in the use of fluorescent chromosome banding, a technique that uses certain chemicals to reveal the unique regions (also known as “bands”) on individual chromosomes. She used this method to study abnormalities in developmental genes, which aided her research in chromosomal abnormalities.

In 1969, Uchida paid a brief visit to the University of London and atomic energy laboratory in Harwell. There, she studied the effects of radiation on mouse eggs and sperm. Following her year abroad, she began working at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario where she founded the cytogenetics laboratory. At McMaster, she was also a professor in the pediatrics and pathology departments until 1991. In 1991, Dr. Uchida began directing the cytogenetics laboratory at Oshawa General Hospital in Oshawa, Ontario. She was appointed to the Order of Canada in 1993 for her “extraordinary contributions to the nation.”

Dr. Uchida passed away on July 30th, 2013 after a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease. Dr. Uchida left a mark on the field of genetics in numerous ways. As an early member of the Canadian College of Medical Geneticists, she helped develop the training of countless laboratory and medical geneticists in Canada. Beginning in 1997, the University of Manitoba has held the eponymous Irene Uchida Lecture every two years, bringing in renowned geneticists to give presentations to pediatricians. A prolific author and researcher, Dr. Uchida published nearly 100 medical papers during her career. Dr. Irene Uchida’s accomplishments have paved the way in cytogenetics, forming the foundation for countless discoveries in the field of genetics.

Why Did I Choose to Research Dr. Irene Uchida?

As a Japanese Canadian female from British Columbia who has aspirations to work in medical genetics, discovering the story of Dr. Uchida inspired me even further to pursue my passions. Learning more about Dr. Uchida’s achievements and incredible contributions to the medical world as a proud Japanese Canadian woman was an incredibly empowering experience, and I hope that her story may inspire and empower other womxn.

Works Cited

Canada, C. (2020). How X-Rays can increase the likelihood of down syndrome in babies | The Channel. Ingeniumcanada.org. Retrieved 27 July 2020, from https://ingeniumcanada.org/channel/innovation/how-x-rays-can-increase-likelihood-down-syndrome-babies.

Davidson, R. (2013). Irene A. Uchida, 1917-2013. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 27 July 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3791260/.

Dickson, K., & Bergeron, J. (2020). Irene Uchida | The Canadian Encyclopedia. Thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 27 July 2020, from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/irene-uchida#.

MLA CE Course Manual: Molecular Biology Information Resources (Genetics Review: Chromosome Band Numbers). Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. (2001). Retrieved 27 July 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Class/MLACourse/Original8Hour/Genetics/chrombanding.html.

Order of Canada. The Governor General of Canada. Retrieved 27 July 2020, from https://www.gg.ca/en/honours/canadian-honours/order-canada.

Plokhii, O. (2013). Irene Uchida, world-renowned leader in genetics research. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 27 July 2020, from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/irene-uchida-world-renowned-leader-in-genetics-research/article14324306/.

Reference, G. (2020). Trisomy 18. Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 27 July 2020, from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/trisomy-18.

science.ca : Irene Ayako Uchida. Science.ca. (2020). Retrieved 27 July 2020, from http://www.science.ca/scientists/scientistprofile.php?pID=21.

Watada, T. (2013). Irene Uchida: Seeing the Truly Wonderful. GREATER TORONTO CHAPTER OF THE NAJC. Retrieved 27 July 2020, from http://www.torontonajc.ca/2013/10/18/irene-uchida-seeing-the-truly-wonderful/.

This article was published on 2/10/21