Simone Veil was born in 1927 on the 13th of July to an atheist Jewish family in Nice, France, as Simone Jacob. Her father, André, had a degree in architecture and married his wife, Yvonne, who had a high school diploma in science. André and Yvonne had four children: Madeleine, Denise, Jean, and finally, Simone. Veil mentioned in an interview that she believed that finishing her high school exams on the 28th of March 1944, caused the Gestapo, which was the official secret police of Nazi Germany, to arrest her and her family two days later. This was because she had to give her name and address in order to complete the exams. At just 17 years old, she and her family were sent to the concentration and extermination camps Auschwitz-Birkenau and later Bergen-Belsen. Veil and her two sisters survived; however, her parents and brother died in the camps.

In May 1945, after the liberation, Veil went back to Paris and began her studies in law at the University of Paris. Then, she enrolled into political science studies at the Institut d’études politiques. There, she met her husband Antoine Veil whom she married in 1946 and with whom she had three children: Jean, Nicolas, and Pierrre-François.

At this time, Veil had practised law for several years, and in 1954 she took the extremely competitive national magistrate exam and passed, allowing her to become a magistrate of the French State. This position of state official allowed her to ensure the improvement of incarcerated women’s rights as well as the improvement of French women’s adoptive and parental rights. The latter entailed that dual parental control of legal family matters was available, as well as rights of single mothers and their children in cases where the father is unidentified, and adoption rights for women. As she said: “true progress for women means recognising that we are all human beings with the same rights and opportunities”.

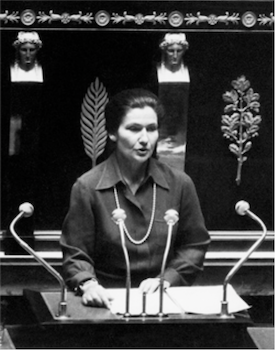

In 1970, she became the first woman secretary general of the Conseil supérieur de la magistrature, which supervises the permanent magistrates, assessors, and deputy judges of the Judiciary Power in France. It ensures the proper functioning of the French jurisdictions and that judges fulfil their duties. In addition, in 1974 she entered the Giscard d'Estaing Government as the Minister of Health, and in that same year, she ensured that access to contraception in France was improved. Veil was the Health Minister until 1979, where she advanced the Loi Veil: a law adopted in 1975 that decriminalised abortion in France. However, this journey was not easy. Veil had to deal with a wave of antisemitism because of her willingness to decriminalise abortion. On top of the Loi Veil, she fought against various forms of discrimination which targeted women, so she managed to set in place health coverage, monthly stipends for childcare, maternity benefits, and several others.

In 1979, Veil was the first woman to be the directly elected President of the European Parliament and the first woman President. This was important, as her Presidential election meant that there was a Holocaust survivor presiding over the European Parliament. Moreover, this position meant a lot to Veil herself as she believed strongly in the European project, especially because of what she had to endure in the concentration camps. She famously said that “freedom is not given to us by anyone; we have to cultivate it ourselves.”

In 1993, she returned to French politics, where she served as the Minister of State and Minister of Health and Social Affairs until 1995. From 2001 until 2007, Veil was the first president of the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah, which is a French foundation commemorating the memory and the victims of the Holocaust. Finally, she was voted into the Académie Française by November 2008, where she was the sixth woman to join the “Immortals”. The “Immortals” in turn are the members of the Académie Française: an institution created in 1635 and meant to define the French language and be its council. The Academy ensures that an official dictionary of the French language is published yearly, and it holds a maximum of 40 members at all times. In her ceremonial sword, which is engraved for every single member of the Academy, she had her Auschwitz tattoo number ‘78651’, the motto of the French Republic ‘Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité’, and the European Union motto ‘United in Diversity’ engraved, demonstrating her commitment to history, France, and the European Union.

Until her death on the 30th of June in 2017, she used her voice and her prominent position at the French Academy to advocate for women’s rights, disability rights, and the rights of HIV-positive individuals. Moreover, she advocated for the European project and for underrepresented groups. This advocacy for women’s health and the European project led to many honours, including the prestigious Charlemagne Prize in 1981, which is given to honour the contributions by individuals to advance the unity of Europe, as well as the Prince of Asturias Award in 2005, which is for advancing international cooperation. Finally, she received a Legion d’honneur in 2012, the highest French order of merit, both civil and military.

Veil was buried in the Panthéon a year after her death, being the fifth woman to be buried there. This honour shows the lasting impact Veil had on recognising women’s rights, and her work regarding contraception, legalising abortion, and standing up for women and minorities.

Why Did I Choose to Research Simone Veil?

I choose to write about Simone Veil because she was such a pioneer in women’s rights. She sparked the beginning of legalised abortion and accessibility to contraception. She is such an inspiration and was an intersectional feminist, stating that in order to get women out of poverty, we need to educate them. She emphasised that racism was debilitating to men and women, but women especially as they endure both racism and sexism. Basically, she helped France forward, and I believe now more so than ever, we need to keep moving forward, ensure women’s rights, and ensure our human rights.

Works Cited

Académie Française. (n.d.). Simone VEIL. https://www.academie-francaise.fr/les-immortels/simone-veil?fauteuil=13&election=20-11-2008

Barthold, C. & Corvellec, H. (2018). For the women - In Memoriam Simone Veil (1927-2017). Gender, Work & Organization, 25(6), 593–600.

European Commission. (n.d.). Simone Veil: Holocaust survivor and first female President of the European Parliament (1927-2017). EU Pioneers.

European Union. (n.d.). Simone Veil: Holocaust Survivor and first female President of the European Parliament. https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/history-eu/eu-pioneers/simone-veil_en

Library of Congress. (n.d.). French Women & Feminists in History: A Resource Guide. https://guides.loc.gov/feminism-french-women-history/famous/simone-veil

Ruth Hottel. (2021). Simone Veil. Jewish Women’s Archive. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/veil-simone

Sara Sherwood. (2017). Biography - Simone Veil : Politician. The Heroine Collective. https://www.theheroinecollective.com/simone-veil/

This article was published on 8/21/24