Ida B. Wells was born enslaved in Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 16th, 1862. However, she had no memory of being an enslaved person, since the American Civil War ended when she was a mere two years old. Wells was the eldest of eight children and, throughout her childhood, her parents, James and Lizzie Wells, highlighted the importance of education; her parents ensured that their children were knowledgeable. Wells enrolled in Rust College, but was later forced to drop out after a confrontation with the university president. After the Civil War ended, the Reconstruction Era began, which consisted of diligent efforts to reintegrate the Southern (pro-slavery) states into the Union, and guarantee freedom to former slaves. Her parents were actively involved in Reconstruction politics.

At the age of 16, her parents and her infant brother tragically passed away after contracting yellow fever. In order to support her orphaned siblings, Wells convinced a school administrator that she was 18 years old and became a school teacher. She simultaneously taught Sunday School, completed household chores, and continued her education. In 1881, Wells moved to Memphis, Tennessee with her two younger sisters, where she continued to teach.

When the Reconstruction Era ended in 1877, Jim Crow laws dominated the American South, with policies upholding racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement. In 1884, Wells purchased a first-class train ticket and sat in the ladies’ car. The conductor told her to move to the train car for African Americans, but she refused. She was forcibly removed from the car as the white passengers applauded. Wells sued the railroad and was victorious at a local level. Unfortunately, her success was short-lived, as the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the decision and sided against her.

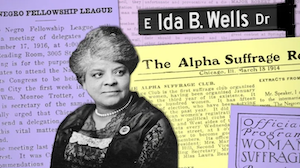

This incident was a turning point in Wells' career. Following the event, Wells began publishing her thoughts, regarding the racial inequities present in the South under the pen name “Lola”. In 1889, she bought a share of the newspaper, The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight. She is often praised for being the first female co-owner and editor of a Black newspaper in the United States. Two years later, in 1891, she lost her job as a Memphis school teacher, after criticizing the segregation policies and conditions within her school district.

In 1892, Thomas Moss, an African American People’s Grocery owner, along with his business associates, were lynched after a series of confrontations with rival white store owners. Because the victims were friends of Wells, this event sparked Wells’ intense battle against lynching. She traveled to the South to gain more information on lynching. In a "Free Speech" editorial, Wells argued that sexual relations between black men and white women were, more often than not, consensual. She added that the lynching of black men oftentimes resulted from white women falsely claiming that they were assaulted. While Wells was in New York, an enraged white mob stormed her newspaper office, destroyed her equipment, and ran her partner out of the city. Afraid to return to Memphis, Wells settled in New York and wrote a lengthy report on lynching for the New York Age, a newspaper owned by former enslaved person, T. Thomas Fortune. In this report, which was reprinted in Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, she asserted that lynching was used to hinder black success.

Wells continued traveling, both domestically and internationally, to publicly denounce lynchings and raise money for her crusade. She brought worldwide attention to the horrors of lynching. In 1893, Wells joined other African American leaders in calling for the boycott of the World’s Columbian Exposition - a fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus' arrival in the New World - after arguing that the exposition shed harmful light on the black community. In 1895, she married Chicago Lawyer Ferdinand Lee Barnett and later gave birth to four children. As she balanced life as a mother and activist, Wells participated in the founding of multiple organizations, such as the National Association of Colored Women (1896), the Afro-American Council (1898), and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1910). Despite facing racism from white suffragettes, Wells was an avid supporter of franchisement for women. On January 30, 1913, Wells co-founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago, which trained women to be involved in politics. On March 25, 1931, Ida B. Wells passed away from kidney disease. She left a legacy of fierce activism and altruism, earning her the Pulitzer Prize on May 4, 2020 "for her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching."

Despite facing racism from white suffragettes, Wells was an avid supporter of franchisement for women. On January 30, 1913, Wells co-founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago, which trained women to be involved in politics.

Why Did I Choose to Research Ida B. Wells?

While completing a homework assignment for AP United States History, I came across the name Ida B. Wells. As mentioned in the article, she was an investigative journalist who continuously risked her life to bring awareness to the injustices faced by African Americans. Her pure selflessness inspired me to set aside time every other week to read about underrepresented African Americans, especially women. I want to acknowledge their efforts to win the unalienable rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” that America's founding fathers promised in the Declaration of Independence. For over 400 years of American history, slavery, racism, and white supremacy has been the focal point of American social, economic, and political life. To this day, as shown in the Black Lives Matter Movement, black Americans are still not treated fairly. The work Ida B. Wells accomplished, such as through the creation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), are vital steps in the long journey to equality. Her achievements should therefore be thoroughly researched and honored.

Works Cited

Ida B Wells-Barnett | Archives of Women's Political Communication. (n.d.). Archives of Women's Political Communication. Retrieved June 19, 2022, from https://awpc.cattcenter.iastate.edu/directory/ida-b-wells/.

Ida B. Wells (US National Park Service). (2020, December 30). National Park Service. Retrieved June 19, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/people/idabwells.htm.

McMurry, L. O. (1999). Wells-Barnett, Ida Bell. American National Biography. Retrieved June 19, 2022, from https://www.anb.org/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-1500924;jsessionid=D71CB69B75335A1685B9754CC6ED1B15?a=1&d=10&n=Ida+B+Wells&q=1&ss=0.

Nettles, A. (2019, November 4). Ida B. Wells' Lasting Impact On Chicago Politics And Power. NPR. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/local/309/2019/11/04/775915510/ida-b-wells-lasting-impact-on-chicago-politics-and-power.

Norwood, A. R. (2017). Ida B. Wells-Barnett. National Women's History Museum. Retrieved June 19, 2022, from https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/ida-b-wells-barnett.

Reconstruction and Its Impact | IDCA. (n.d.). Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs. Retrieved June 19, 2022, from https://iowaculture.gov/history/education/educator-resources/primary-source-sets/reconstruction-and-its-impact.

This article was published on 12/6/22