Yu Gwansun was born on December 16, 1902 in a small city near Cheonan, a city that would later be part of South Korea when the Korean peninsula was divided in 1945 after World War II. She was born the second daughter among five children to parents Yu Jungkwon and Lee Sojae. As a young girl, Yu’s father diligently taught her of Christianity, giving her a strong faith in the religion. Moreover, growing up in a country strongly influenced by traditional Confucious ideals, Yu learned to have great loyalty and pride for her country. At her local church, Maebong Presbyterian, Yu was recognized for her intellect by an American missionary, Alice J. Hammond Sharp, who would applaud her for her extremely quick ability to memorize verses and passages from the Bible.

Although education was something few Korean women prioritized nor partook in at that time, seeing the keen Yu, Sharp referred her to the prestigious Ewha Hakdang School for Girls (Ewha Hakdang). The school was the first modern education institution for women in Korea, established by American missionaries. Despite the abnormality of Yu going to school, her father was one who encouraged her to advance in education. When Yu was thirteen, she moved to the country’s capital, Seoul, in order to attend the school. In 1918, she graduated from the middle school program and began her highschool career at Ewha Hakdang. Then and there, she would be first exposed to the beginnings of the March 1st Movement (or the Samil Independence Movement, “Samil” directly translating to “three-one” or “March one”).

The Samil Movement, starting March 1st, 1919, was a series of demonstrations for the national independence of Korea from Japanese rule. Korea first came under the Japanese military in 1905, when Yu was three years old, and was formally annexed in 1910. The movement began when 33 cultural and religious leaders of Korea signed the “Proclamation of Independence” written by publisher Choe Nam-seon. These leaders organized a mass protest in Seoul in hopes of the national pressure to end colonial power over the country. Protesters during the Samil movement rallied in the streets and shouted out the phrase “Mansei” (“Daehan Minguk Mansei”), which translates to “Long live Korean independence!” The movement centered at Seoul and rapidly spread across the country, becoming a nationwide movement.

Hearing of Samil, Yu and four other fellow Ewha Hakdang High School students participated in one of the movement's most initial activities around Seoul. The next day, Yu and her peers took the streets to Namdaemun Station, a gate in central Seoul. Seeing a student-led demonstration, the protest organizers came to Ewha Hakdang to encourage other students to join. At Namdaemun, Yu was detained for the first time by Japanese authority but was released after missionaries from Ewha Hakdang negotiated for them. Soon after the movement’s spark around the country, on March 10, the colonial government retaliated, requiring all schools to close temporarily.

On March 13, Yu returned to her hometown following the shutdown of her school. Before departing, she smuggled a copy of the Proclamation of Independence with the intent to spread independence spirit in Korea’s southwest region. At home, she informed her family of the rallies that have been happening in Seoul and encouraged them to work towards independence in Cheonan as well. Alongside her father and her younger brother, Yu Jungmu, they went from village to village spreading the word of Samil and assembling residents for their own protests. Yu, with the help of her family, organized a demonstration to be held at the Aunae Marketplace, a small nearby store, on April 1.

The night before the rally, Yu lit a beacon fire, signaling further regions to join the demonstration. The next morning, around three thousand people gathered at the Aunae Marketplace Rally. Yu distributed homemade Korean flags (also known as Taegeukgi), which led the crowd to cheer “Mansei,” and she gave speeches calling for her country’s independence. She even got a speaker to read out the Proclamation of Independence that she smuggled out loud at the rally. The Japanese military police later arrived and began to open shots at the crowd, killing 19 people and wounding many. Both of Yu’s parents were among those murdered.

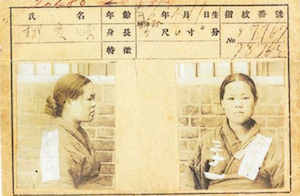

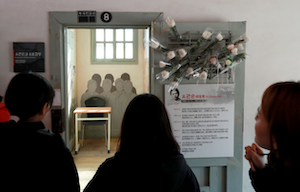

At the premises of Aunae, Yu was captured and soon incarcerated at Seodaemun Prison in Seoul for rebelling against military retaliation since she complained that it was illogical and senseless to not allow for citizens to demonstrate independence. Japanese authorities proceeded to burn the Yu family’s home down. Even in prison, Yu would lead demonstrations with prisoners. For instance, on the first anniversary of the March 1st Movement in 1920, Yu shouted at her Japanese captors when they rudely treated Korean inmates. Due to her continued activism in prison, Yu was eventually transferred to an underground cell where she was repeatedly beaten, starved and brutally tortured. Yu died while imprisoned on September 28, 1920 at the young age of 17 due to the injuries sustained during torture.

After the public announcement of her death, Japanese authorities denied the release of her body, attempting to hide the abuses she suffered in prison. However, after repeated threats from Lulu Frey and Jeannette Walter, principals of Ewha Hakdang, who voiced suspicions of torture to the public, the prison eventually sent over her body in an oil crate. On October 14, 1920, Yu’s funeral was held and she was buried at a cemetery at Itaewon which was later destroyed, resulting in the disappearance of her body.

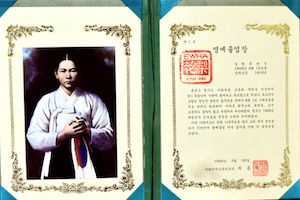

Many years after Yu’s death, in 1989, a memorial was set up on Mount Maembong, where Yu burned the beacon light for the Aunae demonstration, as a “resting place for her soul.” The Korean government awarded the Order of Merit for the National Foundation to Yu on March 1, 1962 for her “outstanding meritorious services in the interest of founding or laying a foundation for the Republic of Korea.” In 1991, the Yu home was reconstructed exactly where it was burned down in 1919 by Japanese authority and was given to surviving members of her family. In 1996, Ewha Hakdang High School awarded her with a honorary highschool diploma and made her birthplace an official sister city of the school.

The paramount goal of Korea’s independence was not able to be achieved solely through the March 1st Movement, yet attempts from passionate people such as Yu was a pivotal point in building national unity, stronger resistance against unjust authority, and drawing in worldwide attention to the situation. Although they are two different countries, March 1st became a national holiday known as “Samiljeol” celebrated in both North and South Korea. Yu never got to see the day of Korea’s liberation on August 15, 1945; however, her impact would last forever, becoming the face of Korea’s fight towards freedom.

Why Did I Choose to Research Yu Gwansun?

My first time learning of Yu Gwansun was at my Saturday Korean School. Since the third grade, the school would celebrate Samiljeol and dedicate that day with interactive, educational activities about the movement for the students. One focal point of this day was learning about Yu and her efforts towards national freedom. Although my younger self would remember every Samiljeol at Korean school as repetitive and tedious, now, I am thankful that I got to know of Yu Gwansun and her story. Despite being a young girl, she was able to accomplish so much for those that couldn’t. She jeopardized and sacrificed her own life for something she loved, her country. As a Korean girl myself, she inspires me to go beyond stereotypical “weaknesses'' and act with unashamed passion for the things I believe in.

Works Cited

Davies, D. (2020). Yu Gwansun - New World Encyclopedia. Newworldencyclopedia.org. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Yu_Gwansun.

Herald, T. K. (2019, February 27). [Eye Plus] Remembering Yu Gwan-sun, icon of Korea’s March 1 Independence Movement. Www.koreaherald.com. http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20190227000831.

Kang, I. (2018, March 29). Overlooked No More: Yu Gwan-sun, a Korean Independence Activist Who Defied Japanese Rule. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/28/obituaries/overlooked-yu-gwan-sun.html.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2019). March First Movement | Korean history. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/March-First-Movement.

This article was published on 2/10/23