He-Yin Zhen was born as He Ban in 1884 in Yizheng, Jiangsu. She adopted the name Zhen (meaning thunderclap) during her time spent in Tokyo. In her published essays, she preferred to sign her name He-Yin Zhen to include her mother’s maiden name in the family name. She was a well-educated woman, as demonstrated by her immense knowledge of traditional Chinese literature in her feminist writing, and attended the Patriotic Women’s School in Shanghai.

In 1904, before her attendance at the Patriotic Women’s School, He-Yin Zhen married Liu Shipei, a famous Chinese classics scholar. Shortly after, they moved to Shanghai, where He-Yin Zhen furthered her studies and Liu Shipei worked for radical causes. In 1907, He-Yin Zhen and Liu Shipei fled to Tokyo to escape retribution for Liu’s anti-Manchu criticisms, which were criticisms directed at the barbaric rule of the Qing Dynasty at the time. There, they joined other Chinese revolutionaries in exile.

In Tokyo, she founded the Nüzi Fuquan Hui (Women's Rights Recovery Association) alongside other anarcha-feminists. The group strived for the suppression of male privilege in society and “interference” with the women that submitted to the oppressive patriarchy. He-Yin Zhen aimed to spread her ideas on women's suffrage and liberation through The Women’s Rights Recovery Association, which also aided members oppressed by their husbands and in their attempts to resist male dominance.

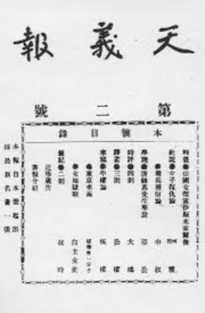

She also established Tianyi Bao or Natural Justice, an anarchist-leaning Chinese feminist journal in which He-Yin Zhen’s writings first appeared. The journal was published by the Society for the Restoration of Women’s Rights in Tokyo from 1907 to 1908. Tianyi offered early Chinese feminist critical analyses of politics, economy, and the patriarchy. The journal became an influential media source for the spread of radical ideas including feminism, socialism, and anarchism.

In the journal, He-Yin Zhen published works such as “On the Revenge of Women,” “On the Question of Women’s Liberation,” and “Economic Revolution and Women’s Revolution,” among others. These writings address suffrage movements in the Western Hemisphere, oppression of women in China throughout history, and social struggles around the world. In her writings, she established new analytical categories, that of nannü, meaning male/female, and shengji, meaning livelihood, which work in conjunction with one another.

Nannü was a critical term in the Chinese feminist discourses of the 1900s. He-Yin Zhen established nannü as a term that encapsulates the international transhistorical relationship between men and women. The idea of shengji is one that is closely tied to the ideas of class, social standing, private property, and labor. He-Yin Zhen attributes female subordination in China to shengji.

Using these two ideas, He-Yin Zhen argued that it is impossible to separate nannü and its patriarchal ties from class, socioeconomic situations, and politics. She concluded that an analysis on women required a social, historical and economic analysis on human life and gender. These ideas are commonly seen in contemporary discourses on intersectionality, seen in the works of bell hooks, Kimberlé Crenshaw and Audre Lorde. Her universally applicable concepts of nannü and shengji pave the way for feminists and radical theorists worldwide.

He-Yin Zhen is speculated to have passed away in 1920. Following the death of her beloved husband in 1919, she is rumored to have died of a disorder and a broken heart. Other rumors claim she became a nun and died soon after there. Though the specific details surrounding her death are hazy, it is clear that her presence and her works left a large impact on feminism.

She is often credited as one of the creators of Chinese feminism, and her work inspired multiple political movements and national projects in following years, such as the May-Fourth Movement in 1919, a movement involving mass protests advocating for socio-political reform, liberation of the individual, and acknowledgement of women, as well as the All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF), a women’s rights organization. Her legacy continues to live on in remarkable Chinese feminists today.

Why Did I Choose to Research He-Yin Zhen?

When I first started reading about Chinese feminism, I encountered He-Yin Zhen’s name a few times and familiarized myself with her ideas. I became more and more interested in her work as I continued reading about Chinese feminism and finally read a few articles on her life and her work. I found myself very interested in her ideas so I decided to research her for iFeminist!

Works Cited

Angela Xiao Wu & Yige Dong (2019): What is made-in-China feminism(s)? Gender discontent and class friction in post-socialist China, Critical Asian Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14672715.2019.1656538

Gao, B. the birth of Chinese feminism: essential texts in transnational theory. Fem Rev 110, e9–e11 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.2015.8

Glosser, Susan J. (2003). Chinese Visions of Family and State, 1915-1953. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 8. ISBN 052-092-639-0.

Karl, R. E., Ko, D., & Liu, L. H. (2013). The birth of Chinese feminism: essential texts in transnational theory. New York: Columbia University Press.

Liu, H. (2003). Feminism: An Organic or an Extremist Position? On Tien Yee As Represented by He Zhen. positions: east asia cultures critique 11(3), 779-800. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/49672.

Menke, A. (2017). The Development of Feminism in China. Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers. 164. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/utpp/164

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2019, February 14). May Fourth Movement. Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/event/May-Fourth-Movement

Zarrow, P. (1988). He Zhen and Anarcho-Feminism in China. The Journal of Asian Studies, 47(4), 796–813. doi: 10.2307/2057853

This article was published on 8/16/20