Dolores Cacuango was born on October 26, 1881 in the Pesillo “hacienda,” or estate, near Cayambe, Ecuador. Her parents were “peones conciertos,” known as the indigenous laborers of haciendas who were at the bottom of the economic scale, working for a small piece of land called “huasipungo.” She grew up uneducated due to a lack of resources, and along with her family, was subject to the oppression of the working class and racial inequities. Cacunago escaped the Pesillo hacienda to Quito, Ecuador before she would be forced into an arranged marriage. She took a job as a housemaid of a military officer, and it was there that she learned how to speak, read, and write in Spanish. She also educated herself on the struggles of indigenous people and peasant farmers in urban and rural environments. With her knowledge, she returned to her hometown to fight for the rights of the working class and, along the way, married Luis Catacuamba. In 1930, Cacunago was a leader in the workers’ strike against the Pesillo hacienda, which was a pivotal event for indigenous and peasant rights. In this strike, she also pushed for better treatment of indigenous women in haciendas who were often raped, beaten, and forced to work without any remuneration, and she protested against the landowners who underestimated the strength of Ecuador’s indigenous people. This strike was so influential that it was a subject in the novel Huasipungo by Jorge Icaza years later.

As a communist, Cacunago was passionate about seeing change in the government and social climate, and she quickly became a prominent figure in the Communist Party of Ecuador. Cacunago continued to be an outspoken activist, and this was especially true during the May 1944 Revolution in Ecuador, when she led an assault on a military base in Cayambe. Her rebellious acts resulted in her imprisonment several times, yet she continued to advocate and fight for the rights of others.

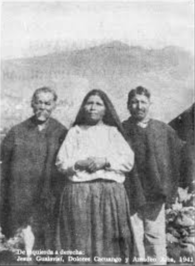

In 1944, Cacunago worked with two fellow activists, Transito Amaguaña and Jesus Gualavisi, to form the Indigenous Ecuadorian Federation (FEI), which was one of the first organizations to defend, demand, and fight for the rights of indigenous people.

Cacunago was also adamant about education for indigenous people. She witnessed how easily and cruelly her people were fooled due to their lack of education, so she founded the first autonomous indigenous school in Ecuador. This first school was formed in Yanahuayco in 1945 and lessons were taught in both the mother language, Kichwa, and in Spanish. The project was extended to other locations, such as Chimba, Pesillo, and Moyurco—all of which had a strong presence of the indigenous movement. By 1963, however, the dictatorship of General Ramon Castro Jijon closed down the schools because they believed the schools were too communistic. The government prohibited Kichwa from becoming a teachable language and even raided Cacunago’s home, forcing her to go into hiding.

Against all odds, Cacunago continued her activism by visiting struggling people during the night and supporting movements in disguise while the government continued to search for her. After a year of underground activities and strong pressure from the people, the Castro Jijon regime was forced to implement an agrarian reform. Cacunago supported this reform—despite its imperfections—and marched 42 miles with more than 10,000 indigenous people from Cayambe to Quito. At the end of the march she gave a historic speech at the University Theater in Kichwa, which included the line: “Somos como la paja del páramo que se arranca y vuelve a crecer y de paja de páramo sembraremos el mundo” [We are like the straw from the fells of the Andes, while you pull it out, it grows again. And with the straw from the fells we shall cover the world].

Dolores Cacuango died on April 23, 1971, surrounded by her husband, son, daughter-in-law, and best friend, María Luisa. The last few years of her life were difficult; she lost strength, weight, and became paraplegic. These conditions limited her from continuing her common visits to communities and organizations. However, her legacy broke down a barrier of oppression in Ecuadorian culture and began the long discussion for the rights of its indigenous people. By 1988, the Ministry of Education in Ecuador recognized the necessity of bettering the education of indigenous people and thus, the National Direction of Bilingual Intercultural Education was created. The city of Quito is reminded of Dolores Cacuango’s efforts by a simple three-block street named in her honor, and the world is reminded of her, surprisingly, through a wasp species also named in her honor, the “Aleiodes cacuangoi.”

Works Cited

Bainbridge, Emma. “Indigenous Women.” Modern Latin America, Brown University Library, library.brown.edu/create/modernlatinamerica/chapters/chapter-6-the-andes/moments-in-andean-history/indigenous-women/.

PeoplePill. “Dolores Cacuango: Ecuadorian Indigenous Rights Activist (1881-1971) - Biography and Life.” PeoplePill, peoplepill.com/people/dolores-cacuango-ruiz-pachacuty-de-la-cruz-urtado/.

Rodas, Raquel. “The Life of Dolores Cacuango And Her Struggle For Justice.” TeleSUR English, TeleSUR, 25 Oct. 2018, www.telesurenglish.net/analysis/The-Life-of-Dolores-Cacuango-And-Her-Struggle-For-Justice--20181025-0029.html.

This article was published on 12/4/20