Eliza “Lyda” Burton Conley was born sometime between 1868 and 1869 to Andrew Conley and Eliza Burton Zane Conley. Her father was an agricultural Englishman and her mother was of the Wyandotte tribe’s chief descent. Conley was raised on a farm in Kansas along with her four sisters, of which she was closest to Ida and Helena. This sisterhood instilled independence in Conley, a trait that is evident in her later actions. By the time she was 16 years old, both of her parents and one of her sisters died. Everyone but her English father were buried in the Huron Indian Cemetery, making the burial grounds not just sacred to the Wyandotte but to Conley as well. As a result, with no parents to support the family, Conley’s eldest sister Ida found work to gain enough money to send Conley to Park University just across the Missouri River, which she crossed every day to attend school. Conley graduated from Park College as a telegraph operator and then found work at Spalding Business College in her home state. Conley continued with this job until it came to her attention that the government wanted to remove the Huron Indian Cemetery, the sacred burial grounds where her mother, sister, distant relatives, and fellow tribal members were buried. Therefore, Conley decided that she would not sit and let her cultural heritage be disregarded.

Immediately upon learning of the government’s plans, Conley took action by moving herself and her sister Helen to live in the cemetery in a makeshift structure she proudly called “Fort Conley” to prevent government intervention; she dutifully lived on the sacred land for the next six years. During that time, Conley also decided to become a lawyer to gain more political traction and power before she argued her case. Accordingly, Conley enrolled in the Kansas City School of Law, graduating in 1902 as one of four women in her class. She was admitted to the Missouri Bar that same year, and eight years later she was admitted to the Kansas Bar as well, becoming the first woman to do so. With her new law degree, Conley took the case to the Supreme Court in Conley v. Ballinger. In this case, Conley argued for the punishment of Ballinger for disturbing Native American lands, particularly Huron cemetery. Beginning at the lower level courts, Conley worked tirelessly to bring her case to the highest trial court in the nation, the Supreme Court of the United States. Doing so was especially difficult due to her unrespected status as a Native American woman, but her perseverance finally earned her the opportunity to reach the Supreme Court. Unfortunately, the court soon reached a unanimous decision that the government had full power over tribal land and could regulate the cemetery as they wished. The Supreme Court’s decision perpetuated the government’s extensive history of Native American land exploitation and the denial of Native American citizenship rights. However, the Court’s decision did not phase Conley, as she continued to live on and defend the cemetery.

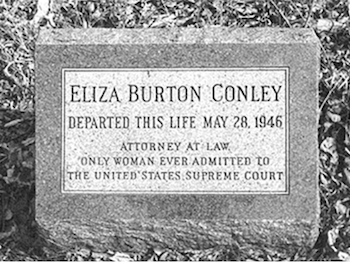

Eventually, Senator Charles Curtis of Kansas saw the cultural value of the land and adopted a bill to protect the area, thanks to Conley’s preservation. The cemetery was ruled to be protected under the same legislation as parks, and the federal government was tasked with helping the state of Kansas maintain the area. Conley was killed on May 28, 1946, and the cause of her death is debated and uncertain. Today, historical researchers argue that her death was either in a library or on her way to the cemetery one day. Both theories involve Conley being hit devastatingly in the head with a rock or another heavy object, providing a death unfit for someone who survived and advocated for so much; however, both possibilities remain in theory until more extensive research can be conducted. To this day, Conley is considered the Guardian of the Huron Indian Cemetery, where she is buried with her gravestone that is marked as a Chief’s would be. Her legacy continues, as the cemetery was named a National Historic Landmark in 2017, and she was recognized as the star of Indigenous People’s Day in 2022. Conley was a trailblazer for Native Americans and women, her influential work making ground for the rights of those marginalized.

Why Did I Choose to Research Lyda Conley?

I chose to research Lyda Conley because I am also a female of Native American descent, and I find it so inspiring that she paved the way for so many in the area of law and advocated for what she believed in front of the Supreme Court. She was a strong feminist and advocate for her tribal heritage. Her determination in the face of adversity motivated me to research her.

Works Cited

Fowler, Russell. “Lyda Conley: Saving Her People’s Heritage.” Tennessee Bar Association, 2023, http://www.tba.org/?pg=Articles&blAction=showEntry&blogEntry=88075

“Indigenous Peoples’ Day Featuring Eliza ‘Lyda’ Burton Conley.” Bureau of Land Management, 2022, http://www.blm.gov/blog/2022-10-14/indigenous-peoples-day-featuring-eliza-lyda-burton-conley

Lacey, Anne. “Know Your KCK History: Lyda Conley.” KCKPL, 2024, http://kckplprograms.org/2020/08/27/know-your-kck-history-lyda-conley/

“Native American Heritage Spotlight: Eliza ‘Lyda’ Burton Conley.” News and Insights, 2018, http://www.tysonmendes.com/native-american-heritage-spotlight-eliza-lyda-burton-conley/

Rothberg, Emma. “Lyda Conley.” National Women’s History Museum, 2022, http://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/lyda-conley

Twain, Laura. “Discovering The Fierce Females of Kansas City, Kansas.” Visit Kansas City Kansas, 2021, http://www.visitkansascityks.com/blog/post/discovering-the-fierce-females-of-kansas-city-kansas/

This article was published on 5/22/24