Born in New Mexico on April 30th, 1930, Dolores Huerta is the second of three children of Juan Fernandez and Alicia Chavez, a miner who would later become a state legislator in 1938 and farm laborer. Her parents would divorce when she was three years old, and her mother would take her and her siblings to Stockton, California. Huerta was cared for by her grandparents while her mother worked as a cannery worker and a waitress. Her mother was highly involved in various civic organizations, community affairs, and the community church, and she was well known for her compassion. As a businesswoman who would later own a restaurant and a small hotel, she embraced farm laborers and other low-wage workers at accommodating prices and even granted free housing.

Huerta’s passion for activism was incited by her mother’s kindness toward others and the various acts of discrimination she would face. She was targeted by a teacher, who was prejudiced against Hispanics and accused her of cheating because of her eloquent school papers. At the end of World War II, her brother was attacked for wearing a popular Latino fashion called a Zoot-Suit.

Huerta began her journey as an activist at Stockton High School and was also an active member of other clubs and the Girl Scouts. She would graduate from San Joaquin Delta College with an associate's degree in teaching. During this period, she married Ralph Head and had two daughters. They ended their marriage later on, and she would marry Ventura Huerta, with whom she had five other children, but also had a divorce with. During the 1950s, Huerta began teaching for a brief time. After being exposed to many hungry farmworker children, she thought that she would be better equipped to organize and advocate for farm worker rights. This led to major dynamic shifts in her family, as the time she would spend with them decreased significantly.

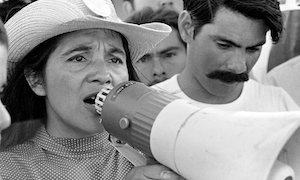

In 1955, Huerta co-founded the Stockton Chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO), an organization that pushed for economic improvements for Hispanics. In 1960, she founded the Agricultural Workers Association (AWA), which would further aid her cause to improve the rights of farm workers. She met Cesar Chavez through another CSO member, and co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) with him in 1962, which would be renamed as the United Farm Workers (UFW) in 1965. As vice-president of the UFW, Huerta continued to organize workers, deliberate business affairs, and advocate for better working conditions for laborers.

In 1965, Huerta supported the workers during the Delano Grape Strike and Boycott with the UFW members and AWOC (Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee) Filipino members, who protested against the use of harsh pesticides on grapes and terrible working conditions. Moreover, in 1973, she helped organize the second grape strike, which ultimately led to the California Agricultural Relations Act of 1975, which declared that farm workers were allowed to strike and protest for better working conditions and wages.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Huerta lobbied for better legislative representation for laborers. In the 1990s and 2000s, she began promoting women's issues and advocated for more Latino and female representation in politics. She has received many awards, such as the Eleanor Roosevelt Human Rights Award in 1998, the Puffin/Nation Prize for Creative Citizenship in 2002, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012, and more. She is the president of the Dolores Huerta Foundation, which focuses on the rights of women, immigrants, workers, and the LGBTQ+ community, and was a board member of the Feminist Majority Foundation. Huerta continues to advocate for the rights of marginalized Americans today and inspires others through her passion.

Why Did I Choose to Research Dolores Huerta?

I chose to research Dolores Huerta because of the lasting impact she left on our society. Her work in the civil rights movement greatly influenced other activists, and her dedication and passion are inspiring, as she put the cause above her own health and family. Huerta is a role model to women of any age, as she still continues to advocate for the rights of others at 92 years old (currently). She is an empowering, inspiring woman.

Works Cited

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2022, April 6). Dolores Huerta. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Dolores-Huerta.

City News Service. (2019, June 22). Civil rights activist Dolores Huerta gets an intersection named for her in Boyle Heights Today. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-dolores-huerta-name-enshrined-in-boyle-heights-20190622-story.html.

Godoy, M. (2017, September 17). Dolores Huerta: The Civil Rights Icon who showed farmworkers 'sí se puede'. NPR. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/09/17/551490281/dolores-huerta-the-civil-rights-icon-who-showed-farmworkers-si-se-puede.

Michals, D. (2015). Dolores Huerta. National Women's History Museum. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/dolores-huerta.

NPS. (2021, August 25). Workers united: The Delano Grape Strike and boycott (U.S. National Park Service). National Parks Service. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/workers-united-the-delano-grape-strike-and-boycott.htm.

Radcliffe Communications. (2019, May 28). Dolores Huerta to receive Radcliffe Medal. Harvard Gazette. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2019/02/dolores-huerta-to-receive-radcliffe-medal/.

Trovall, E. (2019, December 11). ¡SÍ se puede! Houston celebrates Latina civil rights icon Dolores Huerta. Houston Public Media. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/arts-culture/politics-arts-culture/2019/12/11/353553/si-se-puede-houston-celebrates-latina-civil-rights-icon-dolores-huerta/.

This article was published on 1/11/23