Doria Shafik was an eminent Egyptian feminist, a reformer who campaigned for women's rights inspired by feminist pioneer Hudā Shaʿrāwī. She was born on December 14, 1908 in Tanta, Egypt to Ahmad Chafik Sulaiman, who was a civil engineer and of middle-class background, and Ratiba Nassif. Her mother was from a prominent family with high social standing in society. She could not give birth to any male heirs and lost control over her share of her family's inheritance when she was widowed, left with no wealth of her own.

Doria's earliest years were spent in Mansura, where her father worked as an engineer. She then went to live in Tanta with her maternal grandmother, so that she could attend Notre Dame des Apôtres, a prominent French mission school. When Doria was 13, her mother died in childbirth, a searing experience that she recounted in her memoirs: “The loss of my mother left a wound so large that it marked the whole of my life. As an outlet for my despair and desolation, I concentrated all my energy into reading and studying. The result was that I progressed so rapidly that I found myself in the same class as my sister.”

Doria left Notre Dame des Apôtres after her mother passed away and settled in Alexandria with her father and siblings. Girls from middle-class households, like Shafik's, could expect to attend elementary school and then marry and care for the household. However, Shafik knew deep down from a young age that she craved for more, and she commented, "If I were to have a career, I decided it would have to be a brilliant career." Further schooling, however, was only accessible to boys because the city had no girls' secondary education. She persevered in studying on her own and at 16, became Egypt's youngest person to acquire the French Baccalaureate – French A-level. She not only completed the official French curricular examinations ahead of schedule, but also scored among the highest nationwide, awarding her a silver medal.

On the strength of that performance, she sought assistance and support from Huda el-Shaarawi, an aristocrat who had recruited wealthy women to join the Egyptian Feminist Union, which advocated social liberties for women and backed independence from British rule. Unlike Shafik, Shaarawi never advocated for women's political equality and rights and is nevertheless regarded as a heroic figure.

Shaarawi used her position to assist Shafik in gaining a scholarship from the Ministry of Culture, which allowed her to pursue her studies at the University of Sorbonne in Paris. After earning a PhD in philosophy, she returned to Egypt for a few years. which was when she chose to enter a beauty pageant, unknown to her family. Her four years in Paris were transformative in terms of strengthening her already innovative intellect. They shifted her perspective on women's roles in society and set the roots for the beliefs that would later shape her journey. Doria emphasised her excitement in a pageant at the time, saying, "In Paris, I had asserted myself in the intellectual sphere." Now I want to assert myself in the feminine sphere." Although she came in second place for the title of Miss Egypt, her involvement in the competition allowed her to confront views about female figures from her Islamist upbringing.

After a brief and unhappy marriage with an Egyptian journalist that she could not stand for more than a year, Doria met up in France with a cousin that she had not seen for a long time - Nur al-Din Ragai, who was pursuing a doctorate in commercial law in Paris. The two young people found that they had many things in common and decided to get married in Paris in 1937. They had two daughters, Aziza and Jehane.

When Egypt was struggling for independence from British governance, Shafik founded Bint al-nil (Daughters of the Nile Union). In addition, she published a children's magazine "Al-Katkut." She mainly advocated for equal rights of women and aspired for an equal position in patriarchal society. The Bint al-Nil Alliance proclaimed three goals: 1) establish constitutional and democratic rights for all women; 2) promote literacy programs, health and social services to help women; and 3) raise public awareness and knowledge of the conditions of women and children. “No one will deliver freedom to the woman except the woman herself,” Shafik later wrote. “I decided to fight until the last drop of blood to break the chains shackling the women of my country.”

On February 19, 1951, She organized a "feminist congress" at the American University of Cairo, which attracted 1,500 women. However, the meeting was not meant to be a congress - it was just a ruse to fool the police. Shafik established herself as a pivotal figure in the Middle Eastern feminist movement for equal rights. She led the protest through the marble gate of Parliament, which consisted of only men, not a single woman, who decided how a woman should live. A thousand women attacked the Egyptian Parliament, forcing the doors, overpowering the guards, and entering the chambers to shout "Down with the Parliament without women" and "Women’s place is next to yours.". For more than four hours, policymakers around the country were forced to heed women's calls for women's suffrage, women's ability to hold office, and other demands, including equal pay, suffrage, and participation in political life.

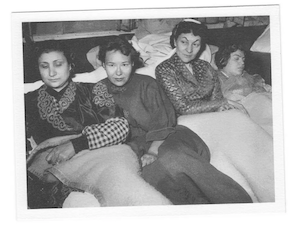

Doria led an isolated hunger strike at a syndicate of journalists in 1954, and fourteen of her colleagues joined her. The strike lasted for ten days in protest of the absence of female representation in the constituent committee, which was created to draft the constitution. She said that women make up half of Egypt and thus, cannot be governed by a constitution in which they had no part. She went on a hunger strike to protest the vacancy of women in the committee which was formed to draft the constitution, the strike lasted for 10 days, during which Doria had to receive medical attention. Doria quickly rose to international fame after the hunger strike caught the attention of the media. The acting president Mohamed Naguib told her that women would have "complete political rights" promising her that they would be given the right to vote. In 1956, women in Egypt were allowed to vote for the first time. She was beginning to be recognized as one of the most important and influential women worldwide. On the contrary, the Egyptian government and media grew less tolerant, and the press started publicly attacking her.

However, it was soon revealed that no one would have such rights. Gamal Abdal Nasser established himself as Egypt's new military dictator, denying both men and women the opportunity to vote in significant elections. Her views and values naturally collided with Nasser. Doria challenged Nasser’s dictatorship head on as it tightened its hold on publications, despite widespread condemnation in the press. She attempted a second hunger strike at the Indian embassy in 1957, but realised she was swimming against the current by herself this time. She asked that the Egyptian authorities terminate their tyrannical reign in a letter to the United Nations. Doria was permitted to leave the embassy without being arrested, but was placed under house arrest as a result of Nehru's personal intervention. The media portrayed her as a traitor.

Embarrassing Nasser in front of the world was an expensive decision for which she paid a heavy price. She had lost her liberty. Her workplace was raided, and her personal records were destroyed. Her journal was banned, her writings were confiscated, her political organization was disbanded, her name was 'wiped clean' from Egyptian newspapers and books. And, of course, she was not allowed to write. Doria was left to fall into darkness and anonymity.

The 18 years leading up to her death were spent out of the public spotlight, in complete seclusion with almost no one by her side. She was never mentioned in the media (a result of direct orders from Nasser) until after her suicide - she reportedly jumped from her sixth story apartment balcony. However, the narrative of her suicide was not without controversy; others questioned it, alleging foul play by the government. Shafik remains a stirring character in Egyptian history; nonetheless, society has yet to come to terms with her kind of feminism. Despite her efforts to reconcile feminism and Islam and to demonstrate their compatibility, she was nevertheless regarded as too contemporary and westernized.

Why Did I Choose to Research Doria Shafik?

Doria Shafik’s name was intentionally and suddenly wiped out by her country’s government and media with no mentions of her heroic demonstrations and impactful role in shaping Egypt’s current condition for women. It is saddening to see that the women in Egypt do not know her tragic story nor the sacrifices she made to enjoy political rights and freedom because of her remarkable achievements. I want her to be known and recognized more in her homeland and to be appreciated for all she did.

Works Cited

Guirguis, S. (2019, February 27). In Egypt, forgotten feminist Doria Shafik brought back to life by Sherin Guirguis. KAWA. Retrieved June 18, 2022, from https://kawa-news.com/en/in-egypt-forgotten-feminist-doria-shafik-brought-back-to-life-by-sherin-guirguis/.

Kinias, A. (2018, December 14). Dinner with Doreya Shafik on her 110th birthday (1908 – 1975). Women of Egypt Mag. Retrieved June 18, 2022, from https://womenofegyptmag.com/2017/12/14/dinner-with-doreya-shafik-on-her-109th-birthday-1908-1975/.

Kirkpatrick, D. D. (2018, August 22). Overlooked no more: Doria Shafik, who led Egypt's Women's Liberation Movement. The New York Times. Retrieved June 18, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/22/obituaries/doria-shafik-overlooked.html.

"Shafik, Doria (1908–1975). Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 18, 2022 from https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/shafik-doria-1908-1975.

Sharaawi, S. (2014). Doria Shafik. Doria Shafik Feminist Activist Egypt, Women Rights. Retrieved June 18, 2022, from http://doria-shafik.com/activist-egypt-womens-rights-memory-07.html.

This article was published on 1/16/2023