Franziska Tiburtius was born on January 24, 1843, in Rügen Island in Pomerania. As the youngest of nine children to poor tenant farmers, Tiburtius was not encouraged from a young age to pursue the lofty goal of becoming a female physician. In fact, Germany did not allow women to become certified physicians until 1899. This did not stop Tiburtius; she was driven and determined, so she was not easily discouraged from overcoming challenges, even if they seemed insurmountable.

Tiburtius initially began working as a governess. She worked in this position, teaching children in private homes, for six years before deciding to pursue another career path. At the time, women had very limited career options, so Tiburtius turned to one of the only acceptable positions for a woman: teaching. She began studying in Britain to become a teacher, but her plans were disrupted in 1871 due to the Franco-Prussian War. Her brother, an army physician, had contracted typhoid during the war, so Tiburtius suspended her studies and returned home to care for him. While helping her sick brother, Tiburtius realized a new calling: she wanted to become a doctor. Despite the restrictions against women throughout Europe, Tiburtius’ brother and sister-in-law, Henriette Hirschfeld-Tiburtius (the first female dentist in Germany), encouraged her to pursue her dream. Unfortunately, German medical schools would not admit her, so Tiburtius decided to attend school in Switzerland at the University of Zurich. In 1876, she graduated from the university and passed all her examinations with distinction. After graduating, she completed a brief internship in Dresden with Franz von Winckel, an obstetrician and gynecologist.

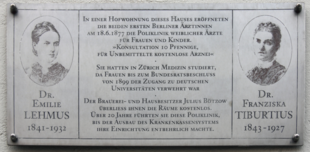

Although Tiburtius was extremely educated and excelled in medical school, she was unable to become a certified physician in Germany because the nation did not allow women to take the exam. She decided to practice as an uncertified but accomplished physician in Berlin, where her supportive brother and sister-in-law lived. Unfortunately, Tiburtius faced a lot of discrimination as a practicing physician, but she never stopped striving to help others in any way possible. In 1877, Tiburtius and Emilie Lehmus, a friend she had met at medical school, opened the Berlin Clinic of Women Doctors, which helped treat poor workers, especially poor women. The clinic faced a lot of public opposition, and most male physicians were completely unsupportive of the practice as well. In fact, the clinic was brought to court several times and repeatedly slandered. However, Tiburtius and Lehmus kept their clinic open for fifteen years and helped countless individuals who might have otherwise been denied treatment due to financial difficulties. The Berlin Clinic of Women Doctors became very popular and treated many patients while also inspiring other female physicians. The clinic also focused on educating other women in medicine to increase the number of female physicians in Germany.

In 1899, Germany finally allowed women to become certified physicians, but by this point, Tiburtius had already been practicing medicine for over two decades. As a result, she chose to continue her career without taking the exam. She believed that she had proven herself through the countless people she had helped, so she did not feel the need to confirm her credibility.

In 1908, Tiburtius founded another clinic, the Surgery Clinic for Women Doctors, with her colleague Agnes Hacker. They made a point to accept female patients without health insurance. The clinic offered free medicine to impoverished clients. Additionally, the clinic employed female doctors who could not find jobs in public hospitals. Tiburtius and her colleagues not only made medical care more accessible to German women, but they also created many opportunities for female physicians. Without general medical clinics hiring women physicians, female doctors were limited to midwifery, which allowed men to completely monopolize the majority of the medical field.

Eventually, Tiburtius decided to retire, and she spent her time traveling throughout Africa, America, and Europe. After retiring from medicine, she also published a memoir titled Memories of an Octogenarian. In 1927, she died of natural causes in Berlin, leaving an enormous legacy of fighting for equal rights to education, career advancement, and health care.

When Tiburtius decided to become a doctor in the 19th century, women in Germany could not become recognized as certified physicians despite receiving the same education as men in medical school. In fact, German medical schools did not even accept women, so they had to travel to foreign universities to earn their degrees. Nevertheless, Tiburtius refused to allow misogynistic statutes to limit her ambition. She inspired women in Germany to pursue medicine and to make healthcare more accessible. Although Tiburtius was extremely intelligent and driven, she had to fight to be recognized as a doctor simply due to her gender. She persevered and encouraged women to advance in the medical field and in every other industry. Throughout her life, Tiburtius created countless opportunities for German women and girls and exemplified limitless ambition.

Works Cited

Franziska Tiburtius. (2020). Retrieved 5 July 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franziska_Tiburtius

McKay, J., Hill, B., Buckler, J., Haru Crowston, C., Wiesner-Hanks, M., & Perry, J. (2014). Understanding western society, combined volume (p. 692). Bedford/St. Martin's.

Meyer, P. (1999). From «Uncertifiable» Medical Practice to the Berlin Clinic of Women Doctors: The Medical Career of Franziska Tiburtius (M. D. Zurich, 1876). Dynamis: Acta Hispanica Ad Medicinae Scientiarumque Historiam Illustrandam, 19, 279-303.

Rappaport, H., & Right Edelman, M. (2001). Encyclopedia of women social reformers (pp. 709-710). Santa Barbara, CA [etc.]: ABC-CLIO.

Roy, R. (2020). Franziska Tiburtius & Aletta Jacobs: European Women Pioneers in Medicine - Rituparna Roy. Retrieved 5 July 2020, from http://www.royrituparna.com/franziska-tiburtius-aletta-jacobs-european-women-pioneers-in-medicine/

This article was published on 2/5/21